1. Introduction

Garbage collection is an essential topic for Java developers, and tuning work in production often focuses on garbage collectors. No single collector fits all workloads, so developers benefit from understanding JVM internals and tuning techniques. ZGC is a newer collector that reduces GC pause times to the sub-second or even sub-millisecond range with minimal tuning.

Oracle introduced ZGC in JDK 11. ZGC was designed with three main goals:

- Support for TB-scale heaps (from megabytes to 4 TB).

- Pause times bounded to around 10 ms (in practice observed at microsecond scale), independent of heap size or live set size.

- Throughput impact below 15%.

This article analyzes ZGC's key algorithmic features and explains how its cycle achieves those goals.

2. ZGC Terminology

- Non-generational: Unlike generational collectors that split the heap into young and old generations, ZGC is non-generational: each GC cycle marks live objects across the whole heap.

- Page: ZGC divides the heap into regions called pages; pages are the unit of reclamation.

- Concurrency: GC threads and application threads run concurrently. ZGC performs most work—marking and heap compaction—in parallel with mutator threads, with only brief STW pauses.

- Parallelism: Multiple GC threads run in parallel to speed up processing.

- Mark-and-copy algorithm: The mark-and-copy process involves three phases:

- Mark: Traverse from GC roots to determine object liveness and mark live objects.

- Copy: Copy live objects to new locations.

- Relocate: Update all pointers that referenced the old addresses to the new addresses.

3. ZGC Performance Data

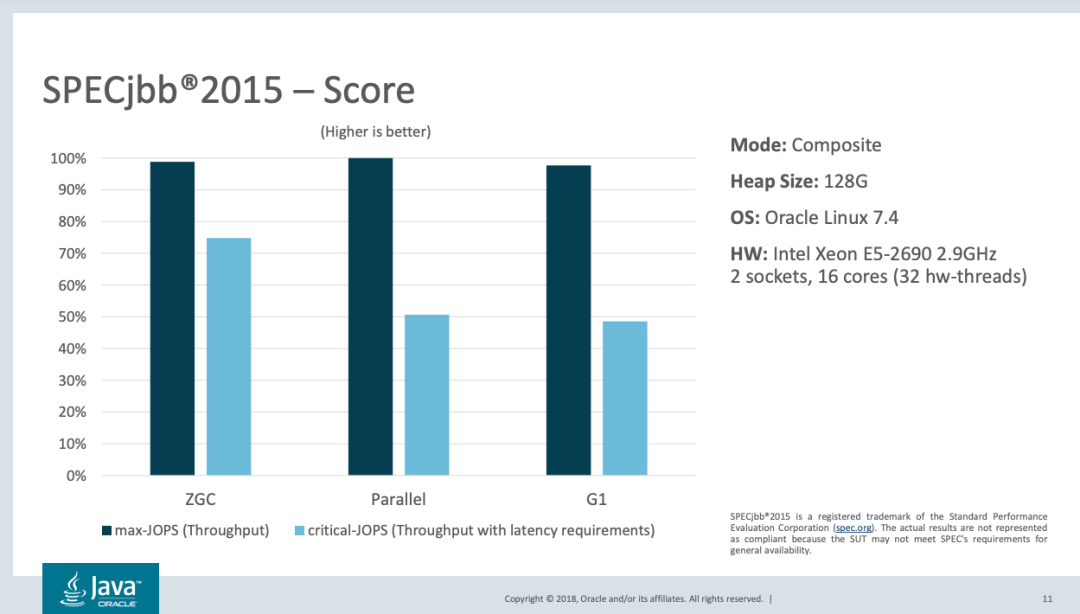

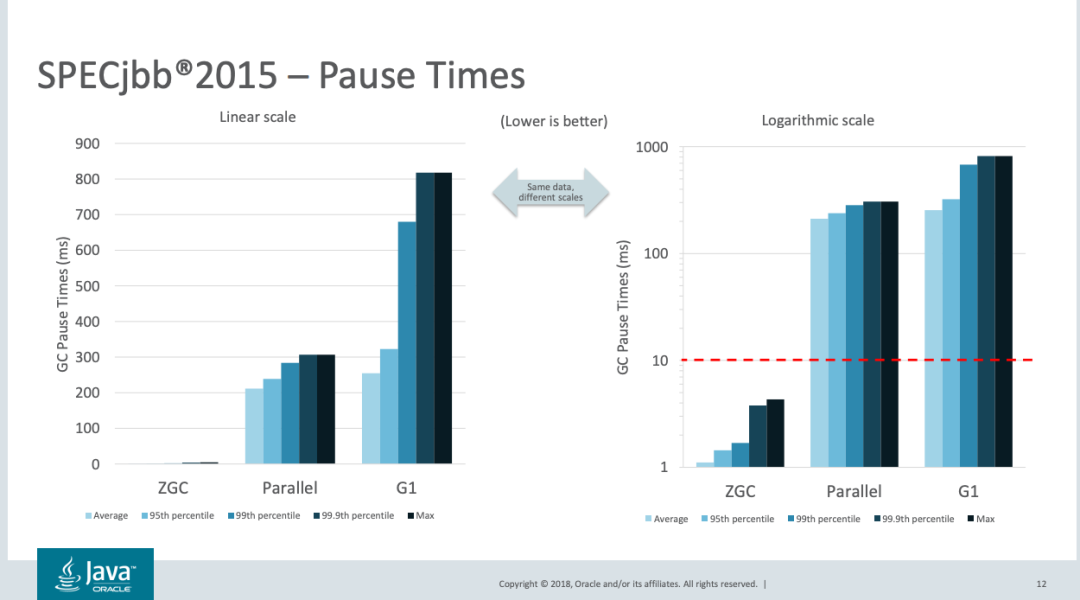

ZGC aims to provide low maximum pause times while preserving throughput. SPECjbb2015 benchmarks on OpenJDK show that with a 128 GB heap, ZGC outperforms other collectors in both latency and throughput.

4. ZGC Key Features

ZGC’s cycle is highly concurrent. Higher concurrency reduces impact on application threads. In SPECjbb2015 ZGC shows orders-of-magnitude lower latency than G1. Only three short STW phases exist in a ZGC cycle; the rest is fully concurrent. This is enabled by ZGC’s improvements in concurrent consistency of heap views.

In concurrent environments threads must agree on shared resource state. Traditional collectors lock or achieve consistency by pausing mutators while GC changes object addresses. During object relocation the old addresses are invalid and mutators cannot safely access objects, hence STW is required in many collectors. ZGC uses colored pointers and load barriers so threads agree on pointer state (color) rather than absolute addresses. This allows concurrent copying and greatly reduces pause times. The next sections explain colored pointers and load barriers, then describe how they are used in the ZGC cycle.

Colored Pointer

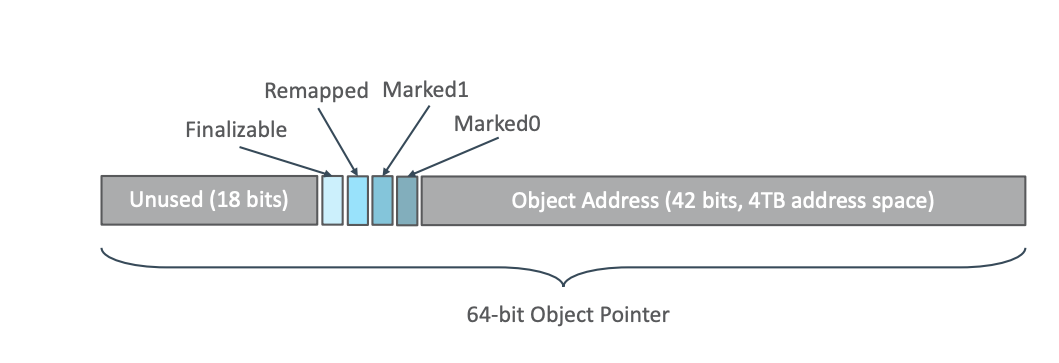

Colored pointers embed metadata in pointer bits (using high-order bits of the address). ZGC pointers are 64-bit values composed of meta bits (pointer color) and address bits. The number of address bits determines the maximum supported heap. With 42 address bits, ZGC supports up to 4 TB heaps. The low 42 bits are address bits, the middle 4 bits are meta bits, and the high 18 bits are unused. The four meta bits represent Finalized (F), Remapped (R), Marked1 (M1), and Marked0 (M0).

ZGC uses pointer colors to indicate whether a pointer is "good" (address valid) or "bad" (address may be invalid). A good color is any state where one of R, M1, or M0 bits is set and the others are unset (for example 0100, 0010, 0001). Color allows checking object state without extra memory access, accelerating mark and copy phases.

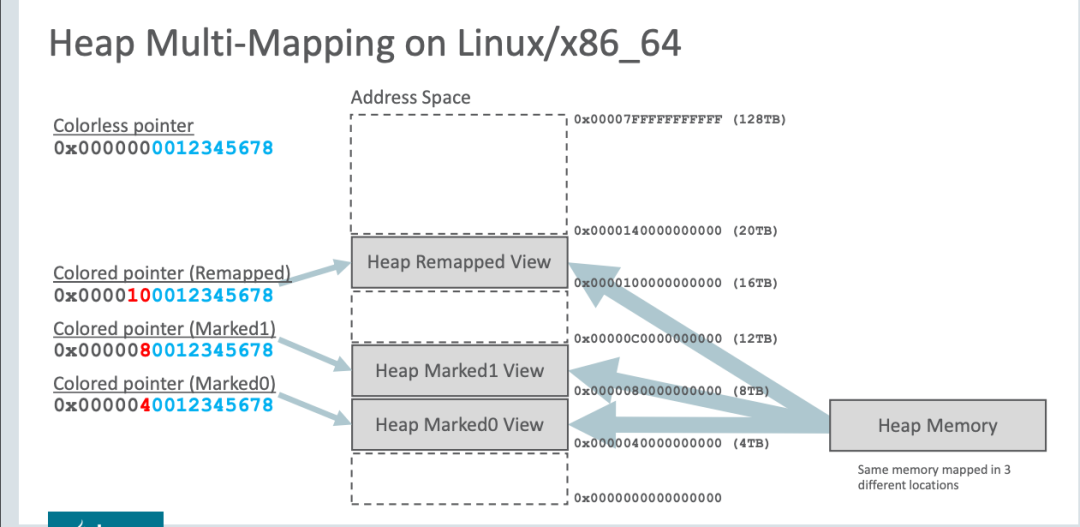

Different meta-bit settings create different address views. ZGC maps the same physical heap into the virtual address space multiple times, producing multiple virtual "views" of the same memory. Only one view is active at a time; ZGC switches view bits to mark object colors during the GC cycle.

- [0, 4TB) maps to the Java heap.

- [4TB, 8TB) is the M0 address space.

- [8TB, 12TB) is the M1 address space.

- [12TB, 16TB) reserved unused.

- [16TB, 20TB) is the Remapped space.

ZGC assigns virtual segments for different parts of the heap. During GC, ZGC scans only the currently active virtual segment and treats other segments as non-scanned views.

Load Barrier

ZGC uses a load barrier (read barrier) rather than write barriers used by earlier HotSpot collectors. The load barrier solves the problem of reading pointers while concurrent relocation is underway. If a mutator loads an object reference while that object is being moved, the pointer could be stale and point to invalid memory. The load barrier detects stale pointers and triggers logic to update them to the object's new location, thereby repairing dangling references.

ZGC tracks object movement with forwarding tables that map old addresses to new addresses. Both mutator threads (on heap accesses) and GC threads (during marking) can trigger the load barrier.

When executing a load like var x = obj.field, the pointer to field is on the heap and triggers the load barrier. The load barrier has a fast path and a slow path. If the pointer color indicates a valid state (good color), the fast path is used, which is essentially a no-op. Otherwise the slow path computes the valid address: check whether the object has been or will be relocated and look up or create the new address. The load barrier also performs self-healing: it updates the pointer in place so future accesses take the fast path. Either path returns a correct address.

/** slot is a local variable on the thread stack, the target object the barrier will operate on */ unintptr_t barrier(unintptr_t *slot, unintptr_t addr){ // fast path if (is_good_or_null(addr)) return addr; // slow path good_addr = process(addr); // self-heal self_heal(slot, addr, good_addr); return good_addr; } /* self-heal, restore pointer to normal state */ void self_heal(unintptr_t *slot, unintptr_t old_addr, unintptr_t new_addr){ if (new_addr == 0) return; while (true) { if (CAS(slot, &old_addr, new_addr)) return; if (is_good_or_null(old_addr)) return; } }

The load barrier can be triggered by GC or mutator threads and is only invoked when accessing heap object references. Accesses to GC roots do not trigger the load barrier; this is why scanning GC roots requires an STW pause.

Object o = obj.FieldA // loading reference from heap, load barrier required Object p = o // no barrier required, not loading from heap o.doSomething() // no barrier required, not loading from heap int i = obj.FieldB // no barrier required, not an object reference

5. ZGC Execution Cycle

ZGC's cycle contains three STW pauses and four concurrent phases: Mark/Remap (M/R), Concurrent Reference Processing (RP), Concurrent Evacuation Choice (EC), and Concurrent Relocate (RE). The following is a simplified description.

Initial Mark (STW1)

Initial mark performs three main tasks:

- Set the active address view to M0 or M1 (alternating between cycles).

- Reassign new pages for application allocations. ZGC only operates on pages allocated before the current cycle.

- Mark root live objects as M0 (or M1) and push them onto the mark stack for concurrent marking.

Concurrent Mark (M/R)

Concurrent marking has two tasks:

- GC threads pop objects from the mark stack and traverse object references to mark reachable objects.

- Compute and update per-page liveness information (active bytes per page) to choose pages for reclamation and relocation.

The following pseudocode sketches the concurrent marking process:

while (obj in mark_stack) { // mark live object; returns true iff object was not already marked and // the current thread successfully set the mark success = mark_obj(obj); if (success) { for (e in obj->ref_fields()) { MarkBarrier(slot_of_e, e); } } } // called by GC threads // EC is the set of pages pending reclamation void MarkBarrier(uintptr_t *slot, unintptr_t addr) { if (is_null(addr)) return; // check whether address points into EC if (is_pointing_into(addr, EC)) { // remap address to current GC view good_addr = remap(addr); } else { good_addr = good_color(addr); } // add accessed object to mark stack mark_stack->add(good_addr); self_heal(slot, addr, good_addr); } // load barrier described earlier, called by mutator threads void LoadBarrier(uintptr_t *slot, unintptr_t addr) { if (is_null(addr)) return; if (is_pointing_into(addr, EC)) { good_addr = remap(addr); } else { good_addr = good_color(addr); } mark_stack->add(good_addr); self_heal(slot, addr, good_addr); return good_addr; }

The mark_obj() function uses atomic operations (CAS) on a bitmap to set mark bits, making it thread-safe. MarkBarrier() processes references and assists GC marking. Concurrent marking runs while mutator threads also run, and mutators help by invoking LoadBarrier() on heap loads.

Remark (STW2)

Remark does three things:

- Fixup tasks for C2-compiled code where missed marks may occur entering remark.

- Drain mutator-local mark stacks to complete marking.

- Perform partial parallel marking of non-strong roots.

Concurrent Evacuation Choice (EC)

EC selects pages to reclaim:

- Identify pages eligible for reclamation.

- Select pages with high garbage density as the evacuation set.

Initial Relocate (STW3)

Initial relocate performs:

- Switch the address view from M0 or M1 to Remapped, indicating relocation is starting; subsequent allocations use the Remapped view.

- Relocate TLABs because their addresses must reflect the new view.

- Begin relocation from roots: traverse root references and relocate the referenced objects.

This STW is proportional to the number of GC roots and is typically short.

Concurrent Relocate (RE)

After initial relocation adjusts root references, concurrent relocation processes each page in the evacuation set EC and relocates objects in those pages.

// GC thread main loop: iterate pages in EC, relocate objects in EC pages for (page in EC) { for (obj in page) { relocate(obj); } } // this method may be executed by GC or mutator threads; if executed by a mutator, // the object will be relocated before use unintptr_t relocate(unintptr_t obj) { // obtain forwarding table for the object ft = forwarding_tables_get(obj); if (ft->exist(obj)) { return ft->get(obj); } new_obj = copy(obj); // CAS to write forwarding table entry if (ft->insert(obj, new_obj)) { return new_obj; } // CAS lost race, insertion failed, free allocated memory dealloc(new_obj) return ft->get(obj); }

The forwarding table stores mappings from old addresses to new addresses. Forwarding table data is stored per-page; after relocation completes for a page, the page's payload space can be reclaimed while the forwarding table entries remain available to repair stale pointers during the remainder of the cycle.

After concurrent relocation finishes, the ZGC cycle completes.

6. ZGC Algorithm Demonstration

The following illustration shows a simplified example of the phases described above.

Summary of the illustrated steps:

- Initial heap state after ZGC initialization.

- Select M0 as the global mark state; mark all root pointers as M0 and push roots to the mark stack for concurrent marking.

- Live objects are painted to indicate they have been marked, independent of pointer state.

- Select pages with the fewest live objects as the evacuation candidate set EC.

- Set global mark state to Remapped and update all root pointers to the Remapped view. If a root points into EC, relocate the referenced object and update the root pointer to the new address.

- Relocate objects in EC; record old-to-new address mappings in the forwarding tables. When concurrent relocation completes, the GC cycle ends and EC pages are reclaimed.

- Start the next GC cycle, selecting M1 as the global mark state (M0 and M1 alternate).

- In the next concurrent mark, references that were stale are resolved by consulting forwarding tables and mapped to new locations.

- Forwarding table entries from the previous cycle are reclaimed after they are no longer needed, preparing for the next relocation phase.

Note: Objects whose pointers remain stale but are not accessed before reclamation are repaired in the next concurrent mark phase when forwarding tables are consulted.

7. Conclusion

ZGC is a complex JVM subsystem. This article focused on two of its key innovations: colored pointers and load barriers, and presented a simplified walkthrough of the algorithm. Studying ZGC illustrates a useful approach to analyzing complex systems: start from the critical workflows and progressively dive into implementation details.

ZGC’s high concurrency enables low pause times and high throughput, enabled principally by colored pointers and load barriers along with other design elements such as its memory and concurrency models and heuristics. Understanding ZGC fundamentals can aid application performance tuning and informed GC selection. ZGC demonstrates strong performance and stability and can be considered when choosing a garbage collector.

ALLPCB

ALLPCB