GCC provides several extensions to the C language standard. This article introduces a number of GNU C extension syntaxes that may include common usages as well as less frequently used features.

Overview

This article covers two extensions:

- Designated initialization

- Statement expressions and their use in macros

1. Designated initialization

In the C standard, a common way to define and initialize an array is:

int a[10] = {0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8};

Using this fixed order assigns values to a[0] through a[8]. a[9] is not initialized explicitly; the compiler will set it to 0.

When arrays are small this initialization is convenient, but when arrays are large and nonzero elements are sparse, assigning values in fixed order becomes cumbersome.

The C99 standard improved array initialization by supporting designated initializers, which do not require elements to be initialized in fixed order.

int b[100] = {[10] = 1, [30] = 2};

Using an element index, you can directly assign values to specific array elements. Designated initialization also works for struct members.

Although early C standards did not support designated initialization, GCC implemented this feature earlier and it is commonly treated as a GNU C extension.

1.1 Designated initialization of array elements

In GNU C you can directly assign values to specific elements using their indexes. Note that assignments are separated by commas, not semicolons.

int b[100] = {[10] = 1, [30] = 2};

To initialize a range of indexes, use the ... range notation:

#include GNU C supports using ... to indicate a range. For example, [10 ... 30] assigns a value to b[10] through b[30]. The range notation ... can also be used in switch-case statements. int main(void) {

int i = 4;

switch(i) {

case 1:

printf("1");

break;

case 2 ... 8:

printf("%d", i);

break;

default:

printf("default");

break;

}

return 0;

}

Note that the ... must be surrounded by spaces on both sides; otherwise a compile error will occur. Similar to arrays, the C standard requires struct initialization to follow the fixed order. GNU C allows using struct member designators to initialize specific members directly. struct student {

char name[20];

int age;

};

int main(void) {

struct student stu1 = {"s1", 20};

printf("%s:%d", stu1.name, stu1.age);

struct student stu2 = {

.name = "s2",

.age = 28,

};

printf("%s:%d", stu2.name, stu2.age);

return 0;

}

The Linux kernel uses designated initialization extensively. For example, many drivers initialize struct members directly: static const struct file_operations ci_port_test_fops = {

.open = ci_port_test_open,

.write = ci_port_test_write,

.read = seq_read,

.llseek = seq_lseek,

.release = single_release,

};

When registering a driver, only some members of a structure such as file_operations may be initialized. Designated initializers make this convenient when structures define many members. Designated initialization is flexible and makes code easier to maintain. In large projects such as the Linux kernel, where many files use this style, designated initializers prevent widespread reordering when members are added or removed. GNU C extends the C standard by allowing statements to be embedded inside an expression. Local variables, for loops, and goto can be used inside such an expression. This construct is called a statement expression: ( { expression1; expression2; expression3; } )

The outer parentheses enclose the statement expression; the inner braces form a code block that may contain arbitrary statements. Like regular expressions, a statement expression has a value equal to the value of its last expression. int main (void) {

int sum = 0;

sum = (

{

int s = 0, i = 0;

for (i = 0; i < 10; i++)

s = s + i;

s;

});

printf("sum = %d ", sum);

return 0;

}

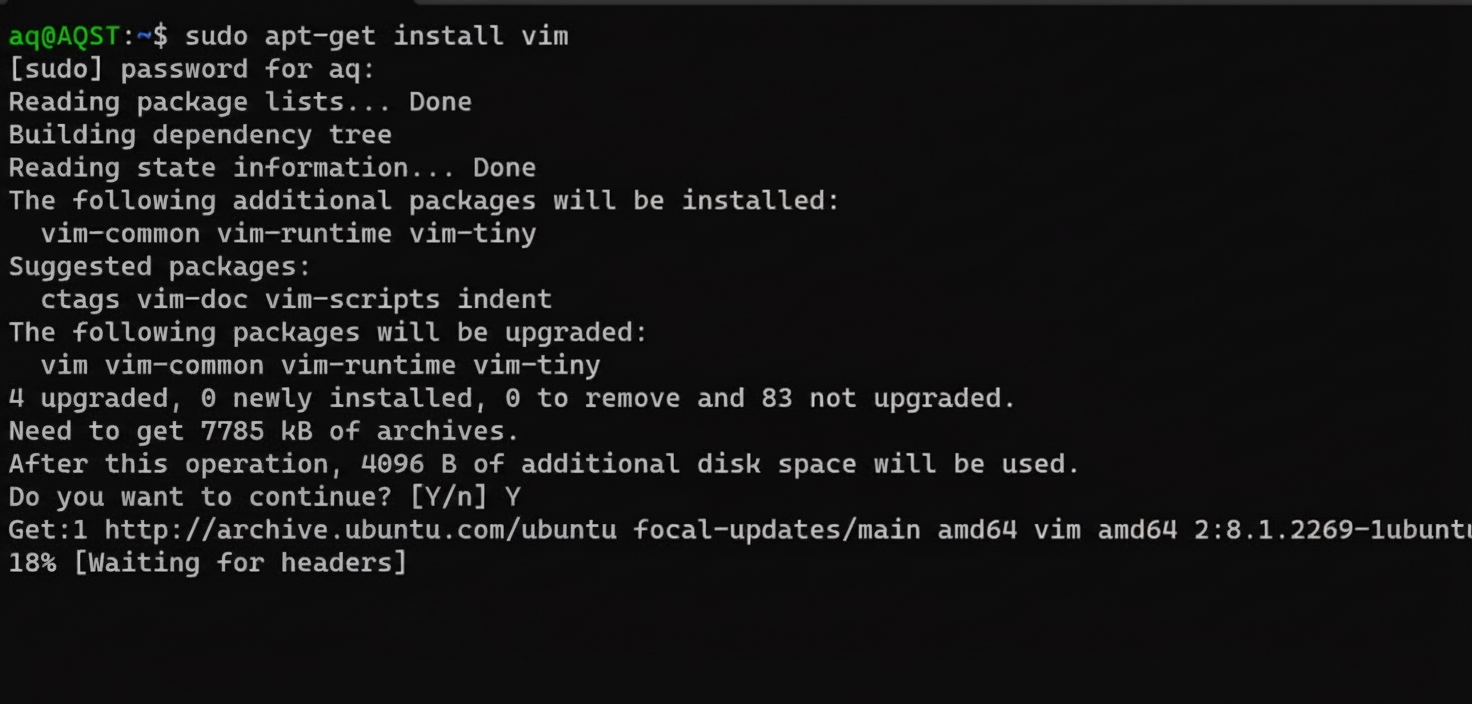

Compile with: gcc -std=gnu89 gnu1.c

/ gcc -std=gnu99 gnu1.c

In the example above the statement expression computes the sum of 1 through 9. Because the value of the statement expression is the last expression in the block, the final s is required after the for loop. If you change that final expression to s = 100, sum will become 100. Statement expressions can also use jumps. int main (void) {

int sum = 0;

sum = (

{

int s = 0, i = 0;

for (i = 0; i < 10; i++)

s = s + i;

goto here;

s;

});

printf("sum = %d ", sum);

here:

printf("here:");

printf("sum = %d ", sum);

return 0;

}

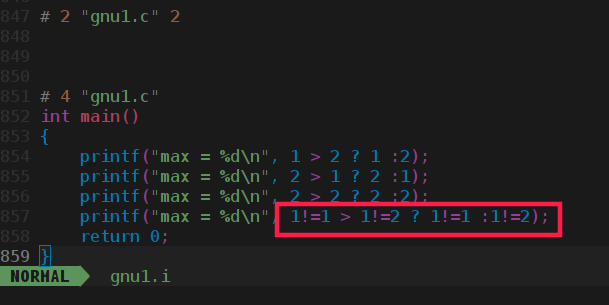

The main use of statement expressions is to define complex macros. Using statement expressions in macros can implement complex behavior while avoiding some ambiguities and pitfalls of simple macros. Example task: define a macro to compute the maximum of two values. Basic: #include <stdio.h>

#define MAX(x, y) x > y ? x : y

int main() {

printf("max = %d", MAX(1,2));

printf("max = %d", MAX(2,1));

printf("max = %d", MAX(2,2));

printf("max = %d", MAX(1!=1, 1!=2));

return 0;

}

The last result may not match expectation. Preprocess the file: gcc -E gnu1.c -o gnu1.i

Because the precedence of > (6) is higher than !=, the expanded expression behaves differently than expected. To avoid this, parenthesize macro parameters: #define MAX(x, y) (x) > (y) ? (x) : (y)

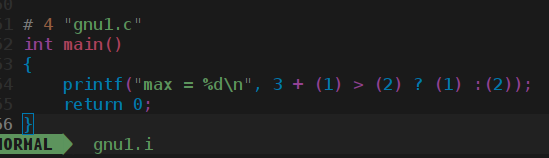

Intermediate: #include <stdio.h>

#define MAX(x, y) (x) > (y) ? (x) : (y)

int main() {

printf("max = %d", 3 + MAX(1,2));

return 0;

}

The expected result is 5, but the actual result may be 1, because + has higher precedence than >. To fix this, wrap the entire macro in parentheses: #define MAX(x, y) ( (x) > (y) ? (x) : (y) )

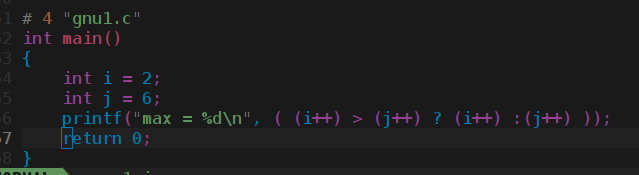

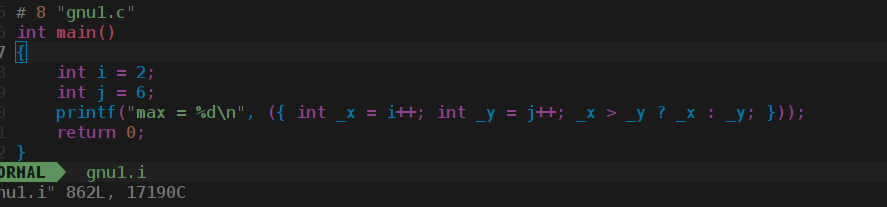

This prevents high-precedence operators outside the macro from altering the intended order of operations. Better: #include <stdio.h>

#define MAX(x, y) ( (x) > (y) ? (x) : (y) )

int main() {

int i = 2;

int j = 6;

printf("max = %d", MAX(i++, j++));

return 0;

}

After macro expansion i and j may be incremented multiple times, leading to unexpected results. Programming guidelines generally discourage macros with side-effecting arguments. To handle cases where arguments may have side effects, use a statement expression that assigns arguments to temporary variables first. #include <stdio.h>

#define MAX(x, y) ({ int _x = x; int _y = y; _x > _y ? _x : _y; })

int main() {

int i = 2;

int j = 6;

printf("max = %d", MAX(i++, j++));

return 0;

}

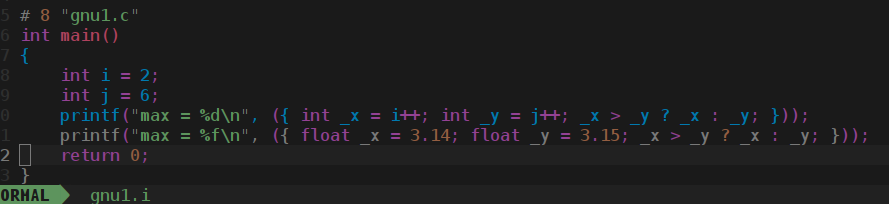

Preprocessing expands this into temporaries so each argument expression is evaluated only once. Excellent: The macro above uses int temporaries, which restricts it to integers. To support other types, pass the type as a parameter: #include <stdio.h>

#define MAX(type, x, y) ({ type _x = x; type _y = y; _x > _y ? _x : _y; })

int main() {

int i = 2;

int j = 6;

printf("max = %d", MAX(int, i++, j++));

printf("max = %f", MAX(float, 3.14, 3.15));

return 0;

}

Further refinement: If you want to keep just two parameters, use typeof to infer the argument type: #include <stdio.h>

#define MAX(x, y) ({ typeof(x) _x = (x); typeof(y) _y = (y); (void) (&_x == &_y); _x > _y ? _x : _y; })

int main() {

int i = 2;

int j = 6;

printf("max = %d", MAX(i++, j++));

printf("max = %f", MAX(3.14, 3.15));

return 0;

}

GNU C provides the typeof keyword to obtain the type of a macro parameter. The expression (void) (&_x == &_y); serves two purposes: This article introduced GNU C extensions: designated initialization and statement expressions, with an emphasis on using statement expressions in macros. In practice, the Linux kernel makes extensive use of GNU C extensions, particularly statement expressions in macros. Familiarity with these GNU extensions can clarify and broaden one's understanding of C.1.2 Designated initialization of struct members

1.3 Designated initialization in the Linux kernel

1.4 Benefits of designated initialization

2. Statement expressions

2.1 Statement expressions

2.2 Using statement expressions in macros

3. Summary

ALLPCB

ALLPCB