Introduction

Population aging is increasing demand for health support, which significantly affects overall healthcare spending. As a result, authorities and insurers place greater emphasis on prevention, health awareness, and lifestyle. Monitoring specific physiological parameters is central to these efforts, which helps explain the revenue growth in smart and health watch products over recent years.

Purchasing a health watch and measuring physiological parameters does not automatically mean healthier living. Long-term monitoring of selected parameters helps users become familiar with their baseline values and adjust daily habits to improve health outcomes. This process can also support a better understanding of how the body functions and how to reduce long-term healthcare costs.

Scope: What, How, and Where We Measure

Wearable devices can measure a variety of important physiological parameters. Depending on the target application, some specifications are more important than others. The placement of a wearable on the body strongly influences which parameters can be measured. The wrist is the most common location, which explains the large number of smart watches and wrist-worn devices on the market. The head is another suitable location; for example, headphones and earbuds incorporate embedded sensors to measure heart rate, blood oxygen saturation, and temperature. The chest is also commonly used: early heart-rate monitors were designed as chest straps using biopotential measurements, which remain a highly accurate technique. Today, adhesive chest patches are gaining adoption because straps can be uncomfortable. Several manufacturers have developed smart patches for monitoring key parameters.

Measurement technology must also be chosen according to body location. For heart-rate monitoring, biopotential measurement is one of the oldest techniques. The signal is strong and can be retrieved using two or more electrodes. This approach fits well with chest straps or ear-based devices. Single-point biopotential measurement at the wrist is practically impossible because the entire cardiac electrical field needs to be sampled. For single-point measurements, optical techniques are more suitable. Light is sent into tissue, and the reflected signal caused by arterial blood flow is captured and measured. From the optical receive signal, beat-to-beat information can be obtained. Although conceptually simple, optical measurement has design challenges such as motion artifacts and ambient light interference.

ADI's second-generation wearable reference platform incorporates most of these measurement technologies. The device is designed to be worn on the wrist, but the strap can be detached so the device can be used as an adhesive patch. The unit integrates technology for biopotential ECG, optical heart-rate measurement, bioimpedance, motion tracking, and temperature measurement in a compact, battery-powered device.

Overall Goals

Why design a system like the GEN II watch? The intent is to measure several important physiological parameters in a simple form factor. The device can measure parameters simultaneously and either store results on an SD card or transmit them via BLE to a smart device. Simultaneous measurement helps identify correlations between multiple signals. Biomedical engineers, algorithm providers, and developers are exploring new technologies, applications, and use cases to detect disease at early stages and thereby reduce later adverse effects.

Single Measurements Are Insufficient

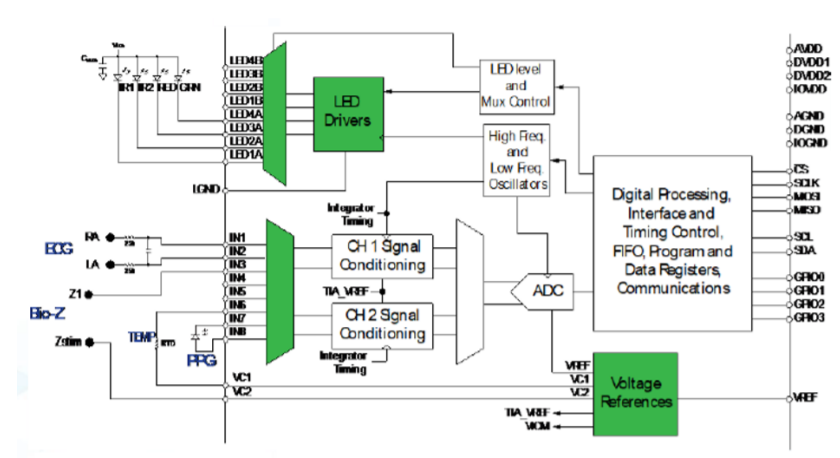

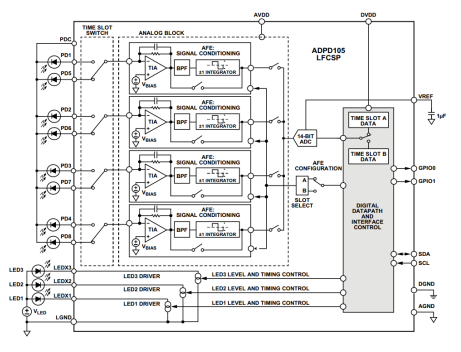

ADI's new wearable system combines embedded sensors, processing capability, and wireless communication. The optical subsystem is built around the ADPD107 optical analog front end. It uses green LEDs to measure PPG and heart rate, and integrates an infrared LED for proximity detection to determine whether the device is in contact with skin. ECG measurement is supported by two independent AD8233 analog front ends. One front end connects to electrodes embedded in the device: a rear electrode contacts one limb and a top electrode can be touched by the other hand to close the circuit. The second analog front end supports ECG measurement via external electrodes, enabling use as an adhesive patch with external electrodes attached directly to the chest.

The rear electrodes also support skin conductance measurement (EDA). EDA, or galvanic skin response, relates to skin conductance changes caused by internal or external stimuli and emotions. The second-generation watch can detect small changes in conductance. The circuit for this measurement is implemented with discrete components and is designed for high accuracy at minimal power consumption. A skin temperature sensor and a three-axis ultra-low-power MEMS sensor (ADXL362) are integrated for temperature and motion tracking. Motion data is used for activity profiling and to compensate for motion artifacts in other measurements. Motion is an important parameter because many metrics, including heart rate, SpO2, and respiration rate, depend on activity and therefore require motion measurement.

For example, a heart rate of 140 bpm during a run is normal, but a heart rate of 140 bpm while sitting may indicate a problem. Combining signals from multiple sensors enables new applications and more context-aware measurements.

The platform integrates an ultra-low-power ADuCM3029 microcontroller for sensor data aggregation and algorithm execution.

Stress and Continuous Blood Pressure

For heart rate, ECG or PPG is sufficient unless motion artifact compensation is needed. Use cases requiring repeated measurements include stress management and continuous blood pressure monitoring. Emotional state can be inferred by monitoring skin conductance changes, which is only one parameter. Combining EDA with heart rate and heart rate variability (HRV) significantly increases diagnostic value. Skin temperature can also be used as an additional input for stress estimation.

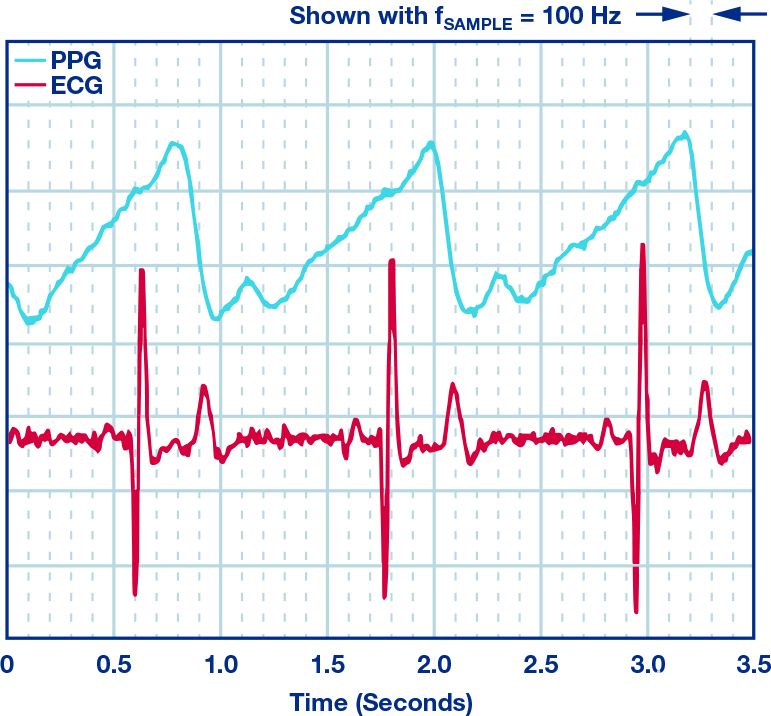

Blood pressure monitoring is an important use case. Most clinically validated systems are cuff-based, which are difficult to integrate into continuous wearable systems. Noncuff techniques exist, for example by exploiting pulse transit time (PTT). Arterial PTT is measured as the time between the R-wave of the ECG (cardiac contraction) and the arrival of the pulse at a peripheral site such as the finger. This transit time is directly related to blood pressure. The watch supports combined ECG and PPG measurements, enabling PTT-based blood pressure estimation.

.Combined ECG and PPG measurements.

From Prototype to Product

The second-generation watch integrates many high-performance sensors and features into a compact wearable. In addition to the electronics, many mechanical design considerations were addressed. This makes the platform relevant for companies designing products for the semi-pro and professional sports markets as well as the medical market. The device can measure multiple parameters simultaneously, but algorithms and software are required to support specific use cases. The reference platform aims to accelerate development by providing a validated hardware baseline for algorithm testing and device integration. A limited number of GEN II watches are available, and ADI is working with design companies and algorithm providers to develop systems intended for professional caregiving and insurer use. Some features already align with medical standards, while others require further development.

ALLPCB

ALLPCB