Overview

This article summarizes common caching issues and mitigation techniques, focusing on two frequent problems: data consistency between cache and database, and cache penetration.

Background

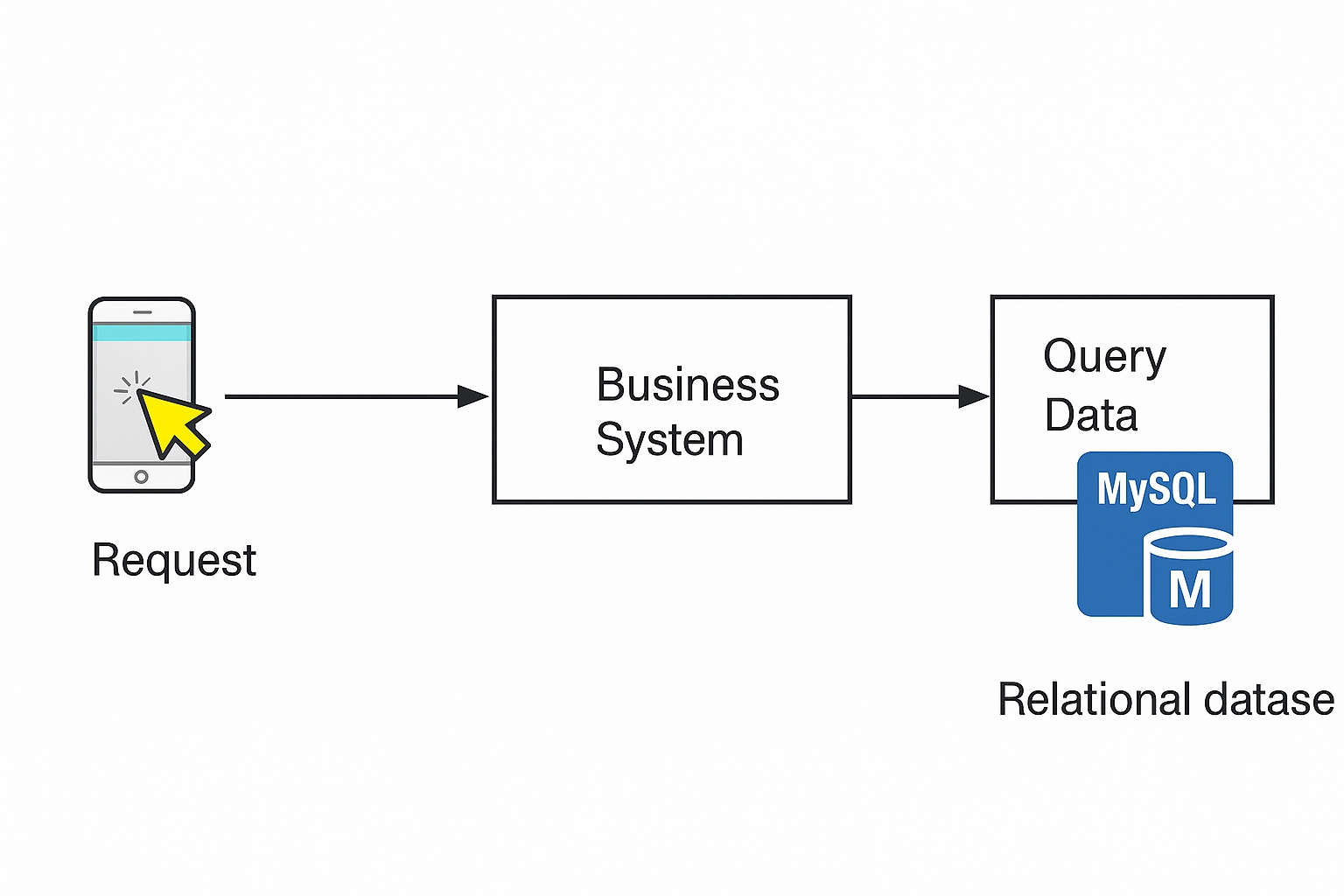

Applications often read and search disk-based data, which leads to frequent database access. As request volume grows, excessive disk reads can become the system bottleneck and may overload the database, causing severe failures.

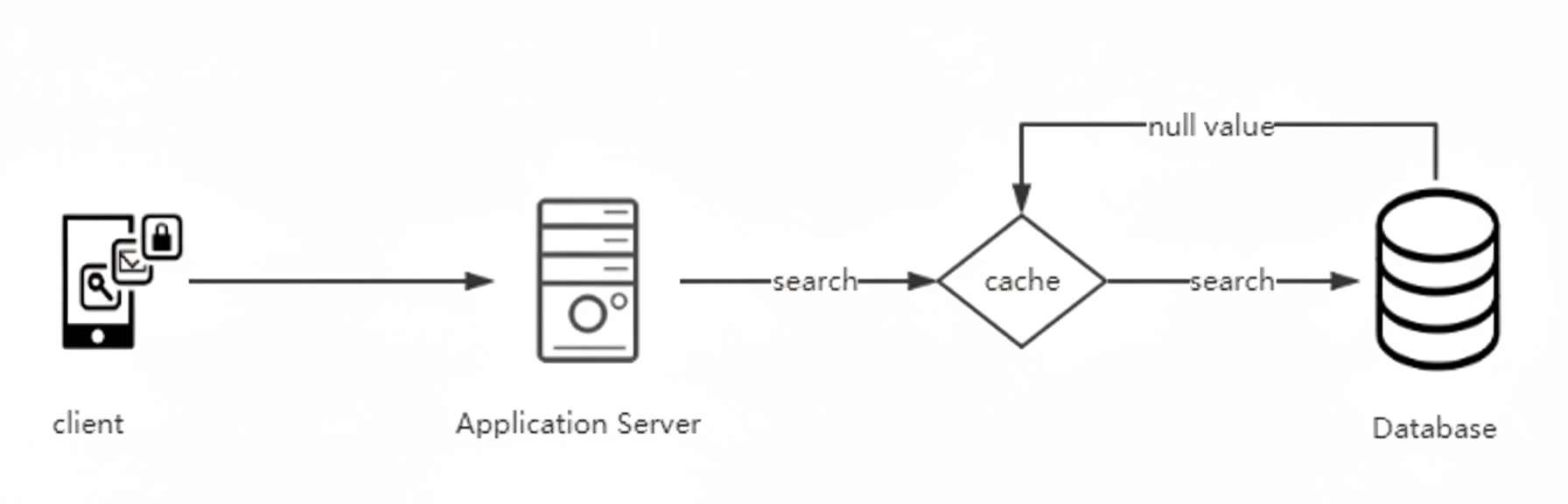

To reduce database I/O pressure, a caching layer is commonly added between the application and the database (for example, MySQL).

When data volumes are high, caching reduces direct database reads and writes.

Common Cache Patterns

Common caching patterns include: Cache Aside, Read Through, Write Through, and Write Behind Caching.

Cache Aside

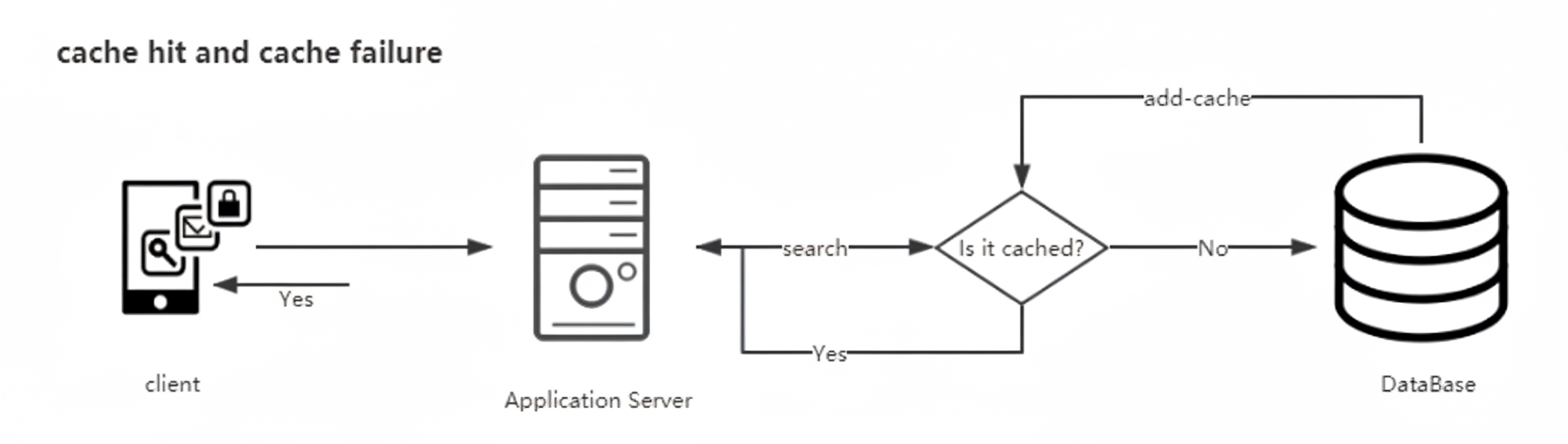

In the Cache Aside pattern, the application checks the cache first. If the cache misses, the application reads from the database and then updates the cache.

Typical scenarios:

- Cache hit: return the value from cache.

- Cache miss: read the source data from the database and populate the cache.

- Cache update: after a write operation updates the database, invalidate the corresponding cache entry.

Cache Aside is widely used, but it is not flawless. For example, a read that misses the cache may fetch data from the database while a concurrent write updates the database and invalidates the cache. If the read then writes the old value back into the cache, the cache will contain stale data.

Guaranteeing full consistency in distributed environments is extremely difficult. The goal is to minimize the likelihood of inconsistency.

Read Through

With Read Through, the application always requests data from the cache. If the cache lacks the data, the cache layer itself retrieves it from the database via a configured provider, updates the cache, and returns the data to the application. This keeps application code unaware of the database and centralizes cache handling, improving code clarity. The tradeoff is that developers must implement the provider plugin, which increases development complexity.

Write Through

Write Through is similar to Read Through. On updates, the cache is updated first; if the cache is present, the cache updates the database on behalf of the application. If the cache does not contain the key, the application updates the database directly.

Write Behind Caching

Write Behind Caching writes data to the cache first and asynchronously persists it to the database. This reduces direct database access and allows batching of multiple updates, improving throughput. However, it carries risk: if the cache node fails before persisting, data may be lost.

Cache Penetration

Cache penetration occurs when a large number of requests query keys that do not exist in the cache or database, forcing each request to hit the database.

Consequences: a sudden influx of such requests can overwhelm the database and cause outages.

Mitigation Strategies

Common solutions include:

1. Null Value Caching

If certain queries frequently return no result and are unlikely to change in the short term, cache the null result for the key. Subsequent requests can be served from cache and avoid unnecessary database queries.

2. Bloom Filter

Preload keys that exist in the database into a Bloom filter. On a request, check the Bloom filter first; if the filter indicates the key does not exist, skip cache and database queries. If the filter indicates possible existence, check the cache, then the database as needed. This prevents non-existent keys from reaching the storage layer.

Cache Avalanche (Cache Stampede)

Cache avalanche occurs when cache nodes restart or many keys expire simultaneously, causing a sudden surge of requests to the backend systems such as the database.

How to Prevent Cache Avalanche

- Locking queue: Use a distributed lock so that when the cache is missing, only the request that acquires the lock reads from the database and repopulates the cache. Other requests wait and then read from cache. This reduces concurrent database reads, but can block many threads and consume memory under heavy load.

- Pre-warm cache and stagger expirations: Proactively populate cache entries before high concurrency periods and set varying expiration times to avoid many keys expiring at once.

- Avoid single points of failure: Improve cache availability with replication and sentinel setups, or use Redis Cluster for sharding and higher capacity. Note that Redis Cluster requires additional nodes and resources.

- Local cache + rate limiting and fallback: Use a local in-process cache (for example, Ehcache) as a last-resort layer if the distributed cache becomes unavailable. Combine this with a rate-limiting and fallback mechanism (such as Hystrix) to protect the database. For example, if 5000 requests arrive in one second and the component allows 2000 through, the remaining 3000 requests are handled by rate limiting and fallbacks, returning default values or degraded responses to avoid overloading the database.

Summary

Different caching patterns have different tradeoffs. Cache Aside is simple but can suffer from race conditions and stale data. Read Through and Write Through centralize cache logic at the cost of additional implementation effort. Write Behind improves throughput but increases risk of data loss. For high-concurrency systems, combine techniques such as null caching, Bloom filters, distributed locking, pre-warming, redundant cache architecture, local caches, and rate-limiting with graceful degradation to reduce the risk of cache penetration, avalanche, and database overload.

ALLPCB

ALLPCB