How moisture affects sensor sensitive elements

As moisture spreads, components or conductive paths that come into contact with moisture on a sensor's sensitive element can cause various functional failures. Moisture can accumulate at epoxy-glass, resin-glass interfaces and in board cracks. Common issues include slower circuit response and delayed device functions; if severe enough, the device may fail to power up.

Tests show sensors exhibit moisture absorption and desorption effects: in printed circuit boards with vias of different densities, trapped moisture desorbs at different rates depending on via spacing. Highly saturated printed circuit boards may require hundreds of hours to dry at elevated temperatures.

If the ambient water vapor partial pressure around a sensor's sensitive element exceeds what the board and components can tolerate, moisture will penetrate. To prevent delamination caused by moisture, soldering processes must meet the following conditions: for high-temperature soldering (about 260°C), printed circuit board moisture content should be below 0.1%; for lower-temperature soldering (about 230°C), moisture content should be below 0.2%.

How does moisture enter sensor sensitive elements?

Common paths

- Cold air contact in winter: In low-temperature environments, the air holds less heat and cannot retain as much moisture, so moisture condenses on cold surfaces. If the device surface temperature of a sensor's sensitive element is lower than the air temperature, it will condense moisture similar to window fogging.

- Assembly process: Water vapor particles in the air can settle on the sensor sensitive element during assembly. If moisture diffuses into internal layers before soldering, the sensor may leave the factory with latent defects. Subsequent drying measures may still expose the board to further moisture risk.

- Baking operations: Baking is a common drying method, but moisture can expand during heating. As temperature rises, moisture molecules inside the sensor can expand rapidly; although most will be expelled, the transient expansion may drive moisture to irreversibly diffuse deeper.

Moisture is a hidden threat to sensors, causing short circuits, reduced accuracy, or permanent damage. Preventing moisture ingress requires a combined approach across design protection, manufacturing processes, and operation and maintenance. The core strategy is a dual barrier of physical isolation plus active management. Specific measures follow.

1. Design stage: block moisture paths at the source

High-level IP protection design

IP rating selection: Choose ingress protection based on the application. For outdoor or underwater scenarios, use IP67 or higher (dust tight, short-term immersion). For humid industrial environments, IP65 (protection from water jets) is recommended.

Seal design optimization: Use threaded seals, O-rings, laser welding, and similar techniques to ensure housing gaps around interfaces and buttons are fully closed. For example, magnetostrictive displacement sensors use multiple sealing rings plus nut fastening to prevent moisture wicking along threads.

Waterproof yet breathable membrane technology

Waterproof breathable membrane: Install an ePTFE membrane at sensor inlets or on housings to allow gas exchange while blocking liquid water and bulk moisture. For example, gas detector sensor heads often use breathable membranes to admit target gases while excluding rain and condensate.

Dust- and water-resistant membrane combinations: In harsh environments with high humidity and dust, add a dust-proof membrane over the breathable membrane to prevent particle clogging while preserving breathability.

Internal moisture-control structures

Built-in desiccants: Place montmorillonite desiccants or molecular sieves inside the sensor cavity to absorb remaining moisture. For example, temperature and humidity sensors often include desiccants to keep internal humidity below 40% RH.

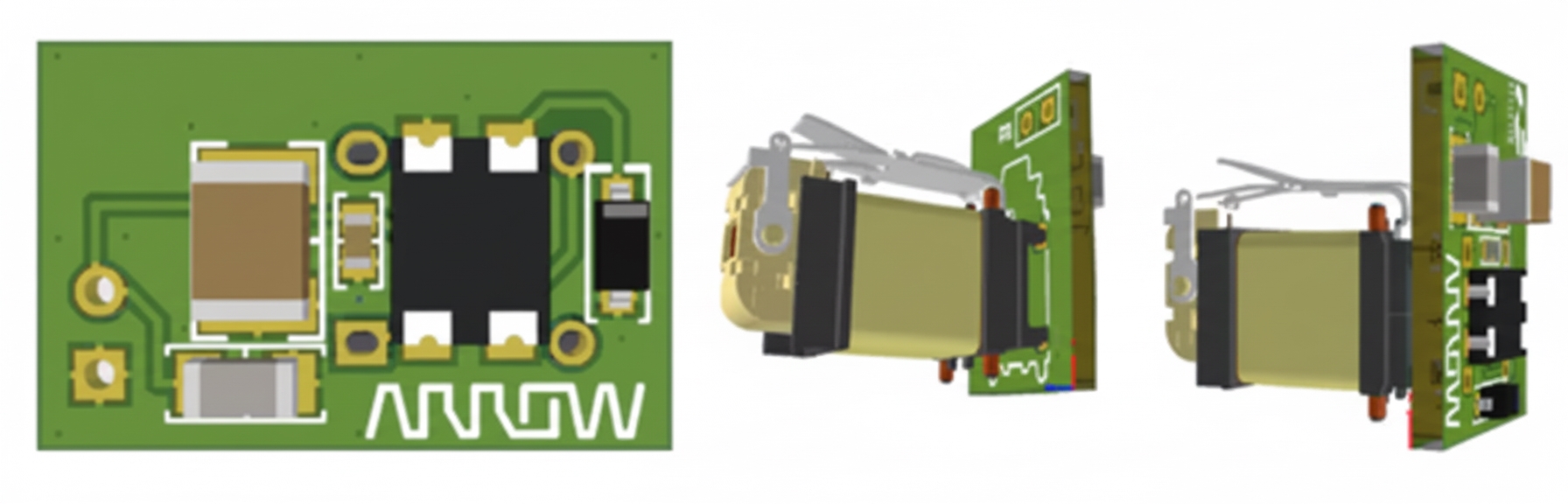

Hydrophobic coatings: Apply nanometer-scale hydrophobic coatings to printed circuit boards and component surfaces (such as poly-p-xylylene or fluorinated coatings) to form molecular-level barriers that prevent moisture adhesion and penetration.

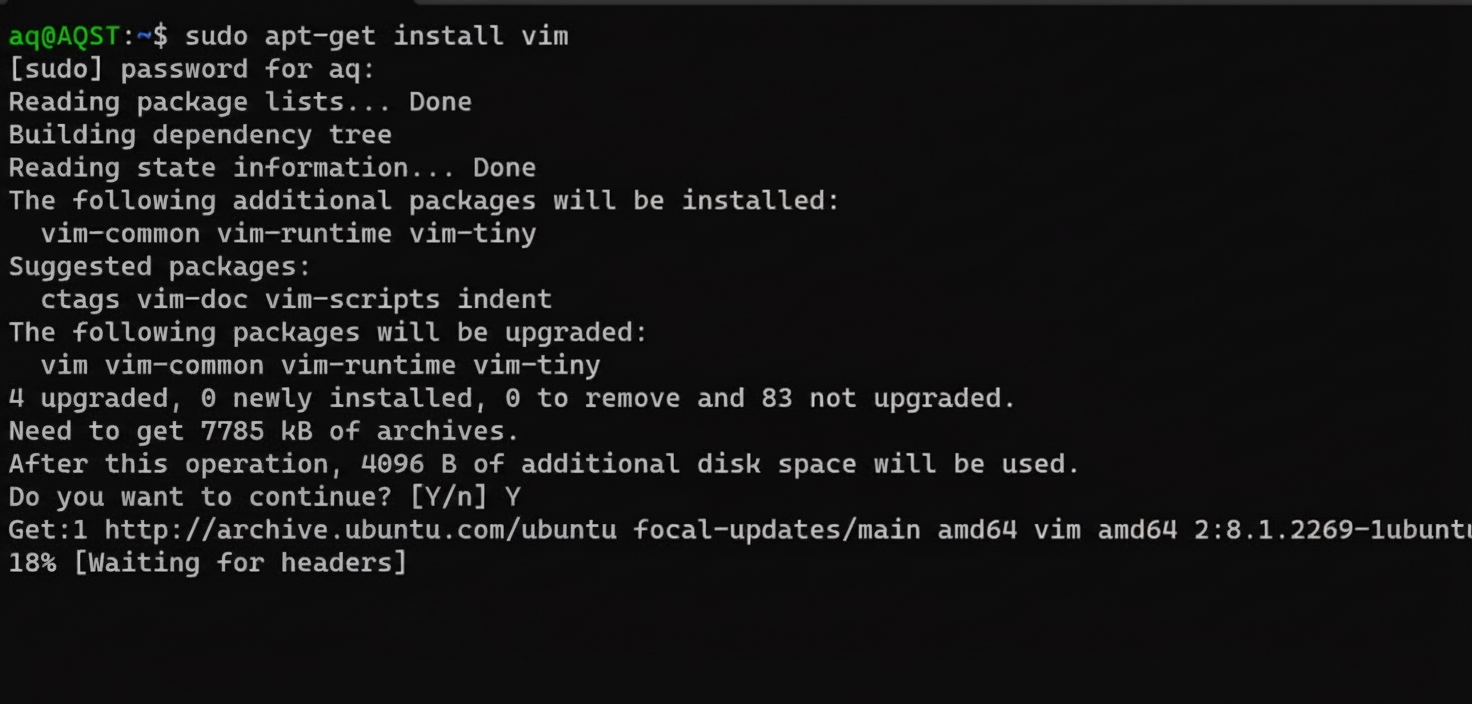

2. Manufacturing processes: strengthen internal protection

1. Replace traditional protection with nano-coating: Use PECVD nano-coatings, which are about 100,000 times thinner than a hair, to form uniform protective layers on sensor chips and printed circuit boards. These coatings address waterproofing, salt-fog resistance, and insulation. For example, nano-coated sensors have remained stable after 1,350 hours immersed in 150°C oil.

Advantages: Compared with potting with epoxy, nano-coatings are thinner (less impact on heat dissipation), easier to service (no need to destroy the encapsulation), and can reduce cost by about 20%.

2. Potting and sealing processes

Flexible potting materials: For sensitive elements such as strain-gauge MEMS chips, use silicone gel potting to provide sealing and mechanical buffering, avoiding cracks from thermal expansion. For instance, some automotive mass airflow sensors use self-healing silicone gel that can recover from minor damage.

Vacuum sealing: For high-precision sensors such as optical sensors, use glass-to-metal welding plus epoxy sealing to create an airtight environment and prevent moisture ingress.

3. Operation and maintenance: dynamic moisture risk management

Regular inspection and calibration

Moisture maintenance: Clean sensor surfaces and inspect seals every 3 to 6 months. Check whether O-rings have aged and whether breathable membranes are blocked. For example, load cells should have their enclosures opened periodically to replace desiccants and test the insulation resistance of strain gauges (should be > 5,000 MΩ).

Humidity compensation: In high-humidity environments, apply algorithms to compensate sensor data for humidity effects (for example, correcting temperature and humidity sensor readings) or increase calibration frequency (for example, gas detectors may go from monthly calibration to biweekly).

Environmental isolation and auxiliary equipment

Protective covers and enclosures: Fit sensors with waterproof housings made of plastic or stainless steel to block rain and spray. For example, outdoor temperature and humidity sensors are often mounted inside a waterproof box with a sunshade while retaining ventilation openings.

Remote monitoring: Place core sensor components such as printed circuit boards in a dry enclosure and collect data remotely via wireless modules such as LoRa and Bluetooth to reduce exposure to moisture.

4. Emerging techniques: active moisture control and intelligent alerts

Self-healing materials

Use self-healing silicone gels or shape-memory polymers that automatically fill and repair microcracks in protective layers, maintaining moisture barriers. For example, sensors on an industrial robot using self-healing gel lasted up to two years in salt-fog conditions, compared with three months without it.

Moisture monitoring and alerts

Integrate a miniature humidity sensor inside the sensor cavity to monitor internal humidity in real time. If humidity exceeds a threshold (for example, > 60% RH), trigger an alert to prompt maintenance. Some high-end pressure sensors include internal humidity-monitoring chips that can push moisture alerts via an app.

ALLPCB

ALLPCB