Introduction

Single-page applications (SPAs) keep code and state in the same page instead of reloading, which increases the importance of memory management. Excessive memory usage can degrade browser performance or cause the page to become unresponsive. This article explains what a memory leak is in JavaScript, how to detect it, common sources in code, and practical ways to avoid it.

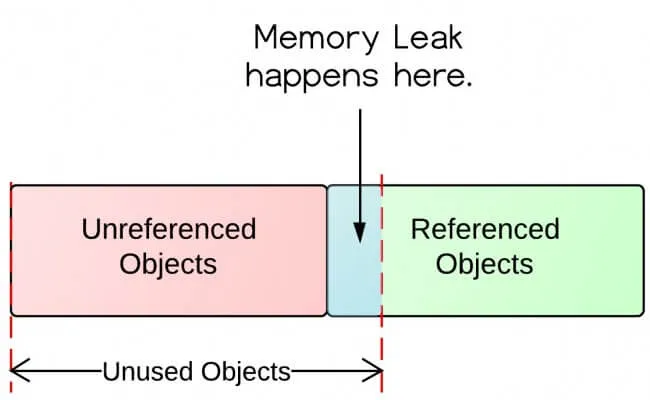

What Is a Memory Leak?

JavaScript objects live on the heap and are accessed by reference. The garbage collector runs in the background and reclaims memory for objects that are no longer reachable. A memory leak occurs when objects that should be collected remain reachable because another live object holds a reference to them. Those redundant objects continue occupying memory, which can lead to increased memory usage and degraded application performance. Regularly releasing unused objects and references helps maintain healthy application behavior.

How to Detect Memory Leaks

Memory leaks are often subtle and hard to spot, and they do not usually trigger runtime errors. If a page's performance degrades over time, use the browser's built-in diagnostics to check for leaks and identify which objects are retained.

The browser Task Manager provides an overview of memory and CPU usage for tabs and processes. In Chrome, open it with Shift+Esc on Windows and Linux; in Firefox, use about:performance or the Performance tools to inspect per-tab JavaScript memory usage. If the application is idle but JavaScript heap usage gradually increases, a memory leak is likely.

Developer tools also offer memory profilers. In Chrome DevTools, the Memory panel can take heap snapshots. Comparing snapshots shows how much memory was allocated between two points and where the allocations occurred, helping to identify problematic objects.

Common Sources of JavaScript Memory Leaks

Finding and avoiding memory leaks means writing code that cooperates with the garbage collector and avoids unintended references. The following are common patterns that cause leaks.

1. Global Variables

Global variables are reachable from the root and will not be reclaimed. In non-strict mode, mistakes can promote local variables to global scope. Two common cases:

- Assigning to an undeclared variable.

- Using this to refer to the global object.

function createGlobalVariables() { leaking1 = 'I leak into the global scope'; // Assigning a value to an undeclared variable this.leaking2 = 'I also leak into the global scope'; // Using this to reference the global object } createGlobalVariables(); window.leaking1; window.leaking2;

Note: Strict mode ("use strict") prevents these errors and helps avoid such leaks.

2. Closures

Variables defined inside a function are eligible for collection once the function leaves the call stack and no external references exist. Closures keep referenced variables alive even after the outer function has finished executing.

function outer() { const potentiallyHugeArray = []; return function inner() { potentiallyHugeArray.push('Hello'); // inner is closed over potentiallyHugeArray console.log('Hello'); }; } const sayHello = outer(); // retains inner's scope function repeat(fn, num) { for (let i = 0; i < num; i++){ fn(); } } repeat(sayHello, 10); // each call pushes another 'Hello' into potentiallyHugeArray // imagine repeat(sayHello, 100000)

In this example, potentiallyHugeArray is never exposed outside the closure but grows with each call. Be cautious about large structures captured by long-lived closures.

3. Timers

setTimeout and setInterval callbacks retain references to objects in their scope, preventing those objects from being garbage collected while the timer is active. A recurring timer callback will keep its scope active as long as the timer is running.

function setCallback() { const data = { counter: 0, hugeString: new Array(100000).join('x') }; return function cb() { data.counter++; // data object is now part of the callback's scope console.log(data.counter); } } setInterval(setCallback(), 1000); // how do we stop it?

To avoid this:

- Be aware of what objects timer callbacks capture.

- Clear timers when they are no longer needed.

function setCallback() { // 'unpacking' the data object let counter = 0; const hugeString = new Array(100000).join('x'); // gets removed when setCallback returns return function cb() { counter++; // only counter is part of the callback's scope console.log(counter); } } const timerId = setInterval(setCallback(), 1000); // save the interval ID // ...do work... clearInterval(timerId); // stop the timer, e.g. on user action

4. Event Listeners

Active event listeners keep their scope alive. An event listener remains active until one of the following happens:

- It is removed with removeEventListener().

- The associated DOM element is removed from the page and becomes unreachable.

Using an anonymous inline function as the listener prevents removeEventListener from working because you cannot reference the same function on removal. If the listener is attached to a persistent object like document, the captured values will remain in memory indefinitely.

const hugeString = new Array(100000).join('x'); document.addEventListener('keyup', function() { // anonymous inline function - can't remove it doSomething(hugeString); // hugeString is now forever kept in the callback's scope });

Prefer named functions so listeners can be removed:

function listener() { doSomething(hugeString); } document.addEventListener('keyup', listener); // named function can be referenced here document.removeEventListener('keyup', listener); // ...and here

If a listener only needs to run once, pass the option { once: true } as the third parameter to addEventListener. The browser will remove the listener automatically after it runs.

document.addEventListener('keyup', function listener() { doSomething(hugeString); }, { once: true }); // listener will be removed after running once

5. Caches

If you keep adding items to a cache and never remove unused entries or limit its size, the cache will grow without bound.

let user_1 = { name: "Peter", id: 12345 }; let user_2 = { name: "Mark", id: 54321 }; const mapCache = new Map(); function cache(obj){ if (!mapCache.has(obj)){ const value = `${obj.name} has an id of ${obj.id}`; mapCache.set(obj, value); return [value, 'computed']; } return [mapCache.get(obj), 'cached']; } cache(user_1); // ['Peter has an id of 12345', 'computed'] cache(user_1); // ['Peter has an id of 12345', 'cached'] cache(user_2); // ['Mark has an id of 54321', 'computed'] console.log(mapCache); // entries for Peter and Mark user_1 = null; // removing the inactive user // Garbage Collector console.log(mapCache); // first entry is still in cache

To avoid leaks from caches, use weak references where appropriate. WeakMap holds keys weakly and accepts only objects as keys. When an object used as a key becomes unreachable elsewhere, its entry can be removed and reclaimed by the garbage collector.

let user_1 = { name: "Peter", id: 12345 }; let user_2 = { name: "Mark", id: 54321 }; const weakMapCache = new WeakMap(); function cache(obj){ // ...same as above, but using weakMapCache... return [weakMapCache.get(obj), 'cached']; } cache(user_1); // ['Peter has an id of 12345', 'computed'] cache(user_2); // ['Mark has an id of 54321', 'computed'] console.log(weakMapCache); // entries for Peter and Mark user_1 = null; // removing the inactive user // Garbage Collector console.log(weakMapCache); // entry for Peter is removed; Mark remains

Conclusion

For complex applications, detecting and fixing JavaScript memory leaks can be challenging. Knowing common causes and following patterns that let the garbage collector do its job are essential. Prioritizing memory and performance ultimately improves user experience.

ALLPCB

ALLPCB