Overview

This application note examines potential attack points throughout a smart meter's lifecycle: manufacturing, installation, operation, and post-installation. It then discusses practical mitigations for these vulnerabilities, such as secure bootloaders during manufacturing, secure metering boards during installation, hardware-based asymmetric cryptography during operation, and potential cumulative attestation kernels (CAK) for forward-looking security. Maxim Integrated's ZEUS SoC is presented as a design example for smart meter security.

Introduction

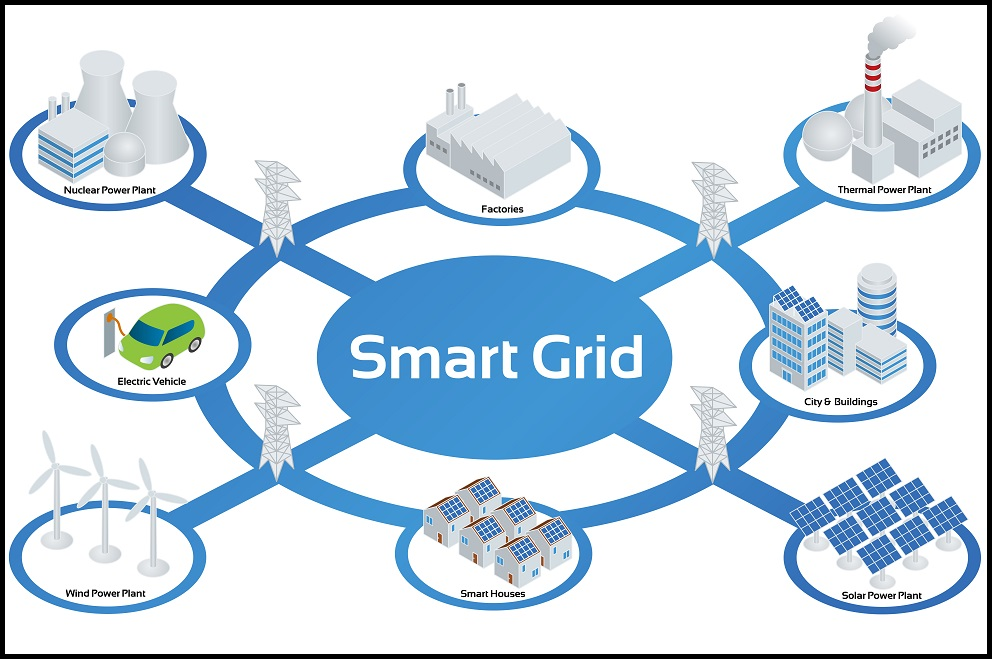

Next-generation smart meters now play a far broader role in the power grid than the early devices that primarily handled communications. Modern smart meters are endpoints in large machine-to-machine networks that connect to smart grid infrastructure and to many future connected devices. Beyond protecting business and consumer data on the grid, smart meters and their infrastructure monitor, control, and in some cases protect critical power systems. Given this expanded role, smart meters introduce new and unprecedented security challenges. Basic encryption alone no longer provides the highest level of protection. Instead, smart meters now require comprehensive lifecycle security from cradle to grave.

This note traces smart meter security threats from manufacturing through installation and initial activation to the device's operational lifetime. It identifies security risks and discusses mitigations for each stage.

Why Secure Smart Meters Are Urgent

Smart grid security has become a significant societal concern. A few years ago, discussions focused on privacy standards and preventing data theft. Today, attention has shifted to threats against societal power systems. Cybersecurity incidents such as Stuxnet, organized meter hacking attacks in regions like Puerto Rico, and other infrastructure threats are frequently reported in mainstream media. To provide necessary system security, many international organizations are developing guidelines and standards for automatic metering infrastructure, including profiles and recommendations from organizations such as BSI and NIST.

Although guidelines describe how security should be architected, actual deployments still lack many critical protections necessary for fully secure smart meter systems. Threats to smart meters are diverse and evolving, so no single final solution exists. Any robust security strategy must adapt to changing threats. Potential problems start with manufacturing, assembly, and calibration, and persist through the meter's expected service life, typically 10 to 20 years for many utilities. Both hardware and software provide mitigation options: hardware is often faster and physically more secure, while software is more flexible. The best balance combines hardware and software measures to protect infrastructure. One such optimized solution is available; the ZEUS SoC is used here as the primary design example.

Securing Manufacturing

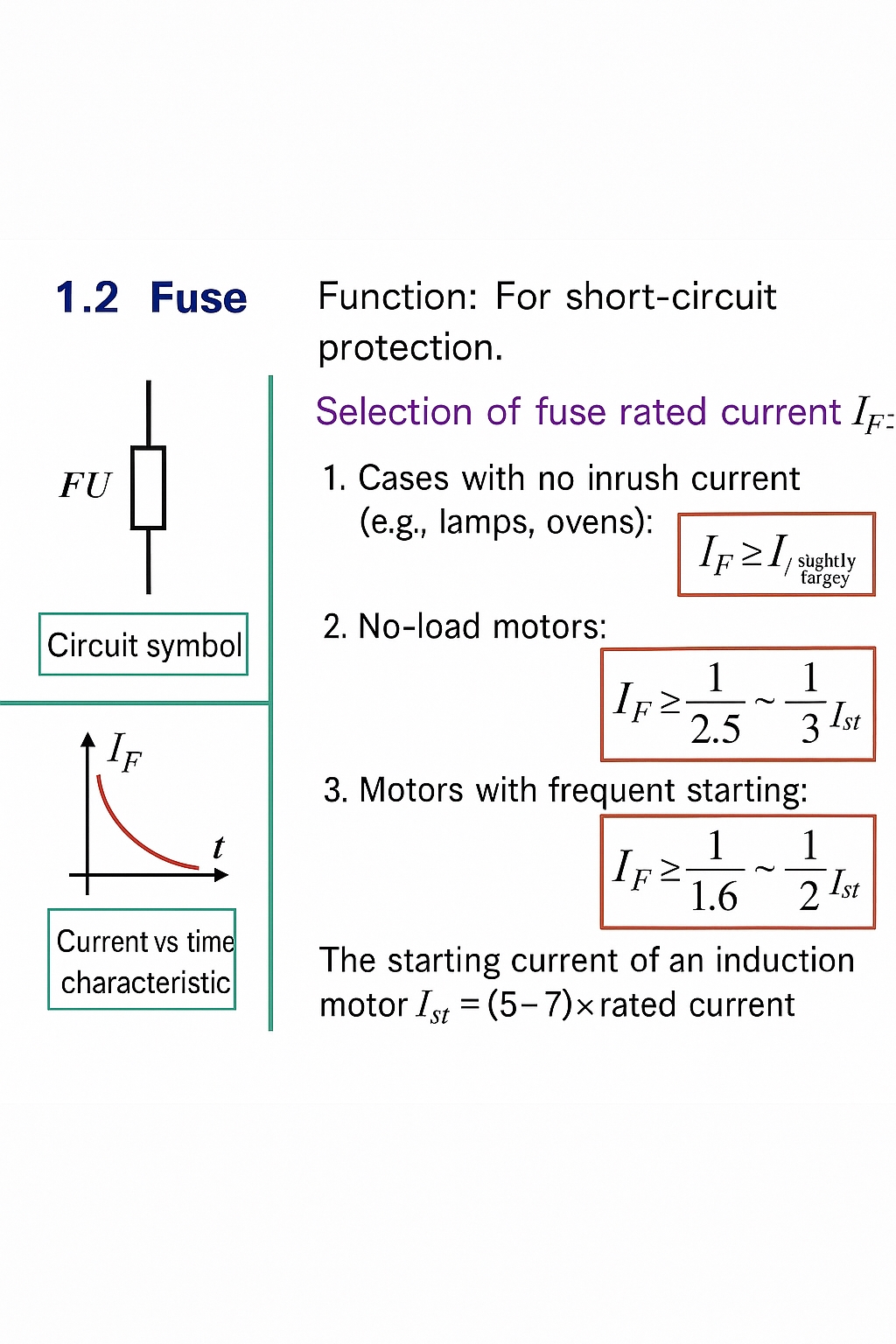

Discussions about smart grid security often focus on cryptographic algorithms used during operation. Encryption is valuable, but it addresses only part of the problem. Encryption protects data in operation but does not resolve challenges encountered during manufacturing and installation. In fact, the manufacturing supply chain is the first potential attack surface.

Like most electronics firms, smart meter vendors rely on contract manufacturers, often in different countries than the design site. While efficient, this model exposes security-sensitive manufacturers to external threats: contract partners can gain detailed knowledge of system architecture, hardware, and software. Therefore, a core principle of secure manufacturing is a trusted supply chain. Security products such as semiconductors should be acquired through trusted channels and authenticated between vetted suppliers and OEMs. Challenge-response authentication using secure hash functions is an effective way to verify supply chain integrity.

Manufacturing processes should restrict access to control systems to trusted parties. Digital signatures and cryptographic algorithms enable this restriction. Reported meter vulnerabilities in some incidents were caused by tampering that likely occurred during manufacturing. One effective mitigation during manufacturing is a secure bootloader.

With a secure bootloader, the OEM controls access to the meter controller during manufacturing. The bootloader validates code loaded during manufacturing at startup. Code is executed only if it is authenticated using asymmetric cryptography combined with secure hash functions, verifying that it comes from a trusted source. An industrial analogy is granting access to a corporate network: only authorized personnel may enter, and only validated commands are executed within the system.

The benefits of a secure bootloader are fundamental. Without a hardware-protected secure bootloader, attackers could exploit a single weakness, such as an exposed key, to compromise the system. For this reason, a secure bootloader is an essential element of modern smart meter design. In such configurations, only parties holding the correct private key and the appropriate trust chain can send messages that the meter will load and execute.

Securing Installation

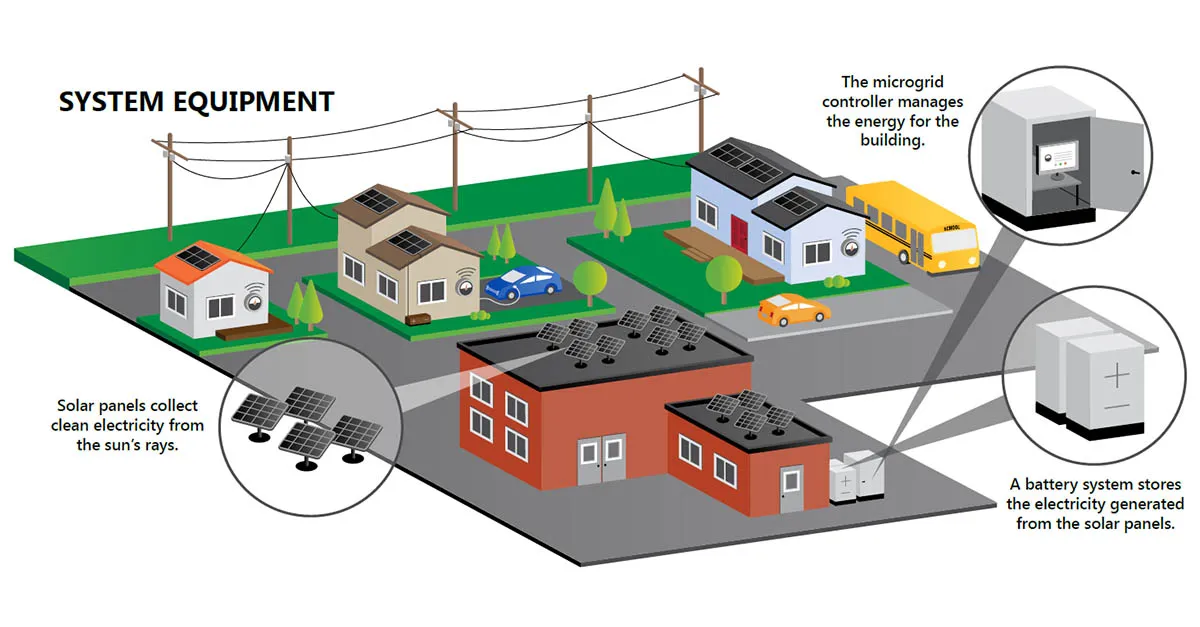

Utilities often do not employ enough staff to install meters quickly, so AMI installations commonly use third-party contractors, creating another handling point for critical infrastructure. During installation, physical attacks such as tampering with optical ports or rewiring can occur. Secure metering can validate installation integrity.

Many meters today use a dual-board architecture: a metering board and a communication board (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dual-board meter where metering data may pass over exposed connector wiring.

Unless the metering function provides its own security, this architecture can run metering data over open lines before encryption is applied. An alternative is a single-board meter that embeds security features within the metering chip itself, such as a secure enclave. On-chip encryption in a dedicated metering domain can encrypt meter data immediately after measurement, closing potential gaps between metering and communication. Data received after installation can therefore be trusted as valid and compared with readings from previous meters to verify correctness. Embedding encryption on the metering chip reduces the attack window between metering and communication and helps ensure data integrity throughout the meter's service life.

Figure 2. Single-board meter with embedded security in the metering chip.

Securing Operation

Meters, and soon many smart devices, are installed outside homes and businesses in physically accessible locations. Attackers have time to study and probe them. Given the scale of the network and the meter's long lifetime, AMI smart meters face threats across space and time.

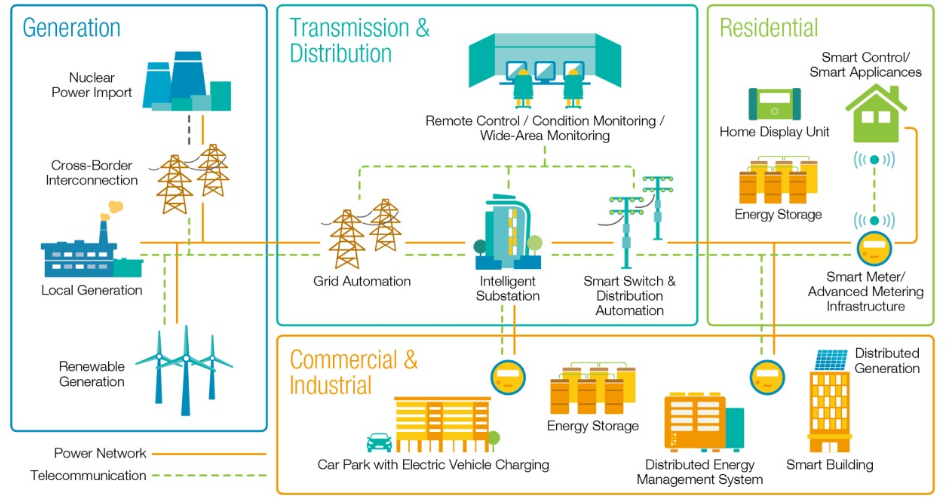

Large Attack Surface

AMI installations have a large attack surface, meaning multiple potential attack points on each meter. Figure 3 illustrates a typical network where hundreds to thousands of meters communicate via power line communication (PLC) or RF to concentrators. Concentrators in turn communicate with the utility over a backhaul such as cellular or fiber. Mesh routing and forwarding between meters and concentrators allow the grid to scale, reducing the number of concentrators relative to meters and lowering infrastructure cost. However, mesh topologies increase vulnerability by creating opportunities to intercept and alter communications between meters, a class of attacks known as man-in-the-middle.

Figure 3. AMI architecture with meters communicating to concentrators via PLC or RF; concentrator backhaul commonly uses cellular networks. Meter-to-concentrator ratios are much lower in this illustration for clarity.

Individual meters generally lack the integrated security features and computational capacity of concentrators or other large network devices, making them easier theoretical targets. Depending on the mesh size, attacks against the mesh can be exploited over a wide area. Because many communications happen meter to meter without supervision from other network infrastructure, each meter requires a strong local security posture.

Equipping each meter with unique security means defining specifications that protect each device individually. Symmetric algorithms like AES provide strong security but typically require a shared key across many meters. If a private key is discovered, an attacker could compromise all meters sharing that key. Asymmetric cryptography is a better approach for unique per-meter protection because each meter uses a unique key pair for encryption and decryption. Keys used for multiple security events, such as authentication, should be generated on-chip, stored in secure storage, and embedded in the device so the private key never needs to leave the meter. Requiring unique key pairs per meter limits the impact of a compromised private key to a single meter. Asymmetric cryptography thus reduces the AMI attack surface and lowers attackers' potential return on investment.

Asymmetric cryptography is computationally intensive, and time-sensitive systems cannot be slowed. Hardware accelerators provide significant advantages: implementing cryptographic operations in hardware reduces computation time compared with software-only implementations and frees system software for other tasks.

Hardware designs that integrate multi-layer asymmetric cryptography along with secure key generation and storage, supported by a true random number generator to prevent key replay, provide a layered approach to security. Symmetric algorithms such as AES can be used in combination with asymmetric methods to meet encryption requirements and applicable standards.

Flexibility to Address Future Threats

Secure smart meters must be flexible enough to address threats that emerge years after deployment. Detecting and mitigating threats over a meter's long service life is therefore a key challenge.

Utilities cite cost and lack of mature solutions as reasons many AMI deployments lack intrusion detection. Meter vendors must answer a practical question: how much processing capability should be embedded in a meter to enable threat detection? Academic work proposes both meter-based and network-based detection approaches. A promising on-meter approach is a cumulative attestation kernel (CAK), a metering-based algorithm that audits firmware revisions and provides an additional detection layer when cryptographic and authentication checks fail. CAK can run on 8-bit or 32-bit microcontrollers with minimal memory. Experts recommend that smart meters include some advanced functionality to provide security and adapt to future solutions.

Response is as important as detection. Many security systems, such as financial terminals, shut down when compromised to prevent further access. For a smart meter, which is the primary power supply measurement device for a customer, immediate shutdown is rarely the best response. Networks must evaluate potential threats and prioritize responses without unnecessarily disrupting service. A meter-level response should balance local consequences against broader network impacts: service interruptions for individual customers are usually less severe than large-scale disruptions or abuse of the communication infrastructure. Therefore, meters should support prioritized defensive responses at runtime.

Meters must provide strong hardware security to mitigate threats while enabling future software-based solutions without extensive hardware changes. Architectures that separate metering functions from general-purpose processing can maintain uninterrupted metering while allowing the processor to handle security-related tasks and future features such as CAK. For example, integrating a 32-bit ARM core for application processing alongside dedicated metering hardware enables untrusted or unauthenticated communications to be ignored, logged, or reported at the architect's discretion. Metering isolation ensures core metrology routines remain uninterrupted, complying with standards that require separation between metrology and non-metrology software. Hardware security accelerators process communication cryptography quickly, freeing the ARM core to run system tasks and future security modules. This combination of computational capability and hardware security, together with appropriate software updates, provides an efficient and adaptive security posture.

Outlook

The smart grid represents a major transformation of 20th-century power systems. Adding networked control and monitoring features increases exposure and vulnerability to attacks, especially cyber threats. International bodies are developing performance standards, and incidents continue to appear in news coverage. Meter manufacturers must defend against attacks throughout the device lifecycle: sourcing, manufacturing, installation, and long-term operation. A prudent approach separates hardware and software responsibilities, ensuring lifecycle security from third-party component procurement through manufacturing, installation, and ongoing operation. Based on current understanding of smart meters and the evolving power sector, Maxim Integrated designed the ZEUS SoC as an example solution for contemporary and future smart meters.

ALLPCB

ALLPCB