Background

I have worked in embedded software development for six to seven years, covering BSP, drivers, application software, Android HAL and framework. I follow developments in the embedded sector and also pay some attention to web back ends, distributed systems, and related technologies.

Recently I considered switching to back-end server development. Although I had followed topics like NIO, epoll, nginx, zeromq, libevent, libuv, high concurrency, distributed systems, Redis, Python, Tornado, and Django, my practical experience in those areas was limited. Unexpectedly, I often encountered condescension from the internet industry and had few interview opportunities.

Why are there few embedded software architect positions?

Searches on job sites return many system architects, web architects, and back-end architects, but embedded software architect roles are rare. Does embedded software or driver development not need architecture? Of course it does, but why are there so few positions titled that way?

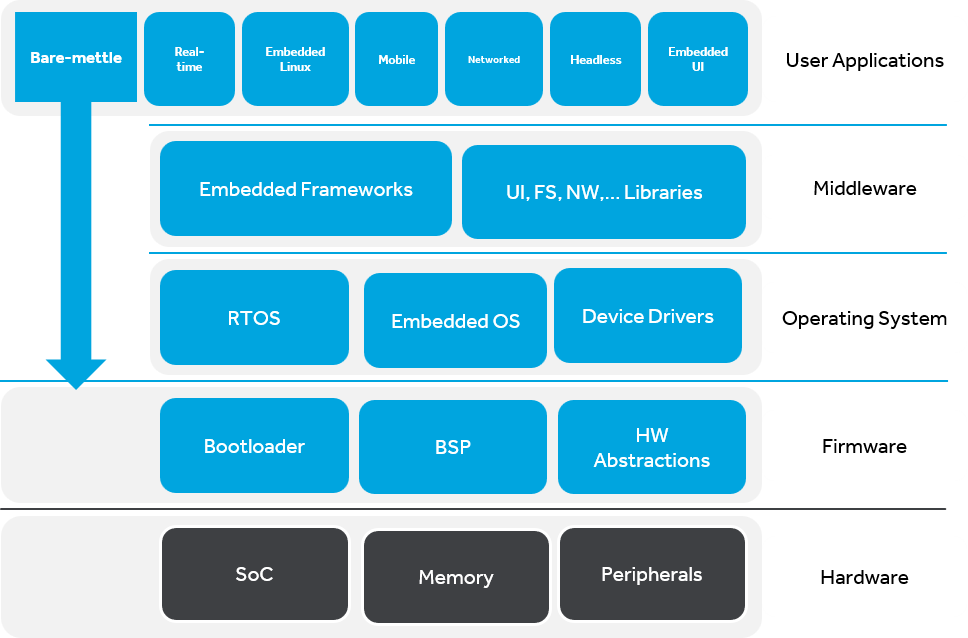

My view is: currently in China, embedded development is mainly divided into low-level embedded development and embedded application development. Low-level embedded development typically refers to driver development or BSP development, and sometimes is called Linux kernel development.

The Linux kernel architecture and operating system architecture are already defined by kernel maintainers such as Linus Torvalds. Because the kernel is a general-purpose platform that addresses general problems, the open-source community has established architectural rules. For most projects, work consists of filling in or adapting to that framework rather than designing a new architecture from scratch.

Also, for many companies in China, the typical business needs are peripheral integration, platform porting, and trimming the embedded platform. Business requirements rarely exceed what the kernel provides. As a result, there are few new architectures that require developers to design and implement at the architectural level.

So what do BSP developers do? Besides debugging a wide variety of peripherals and supporting the hardware team, much of the work is fixing stability bugs. Debugging peripherals increases breadth of experience but contributes less to deep architectural reasoning. Application-level embedded development often involves relatively simple business logic and is sometimes overlooked, which reduces the perceived need for architect-level roles.

Therefore it seems understandable that embedded development has fewer formal architect positions and that some internet-sector employers may undervalue embedded experience. That said, there are developers in China who can propose architectural optimizations for the kernel and driver architecture, but they are relatively rare. For most engineers, focusing on uncovering and solving bugs is the more realistic path than aiming to become a Linux kernel architect.

Do we really not need architecture?

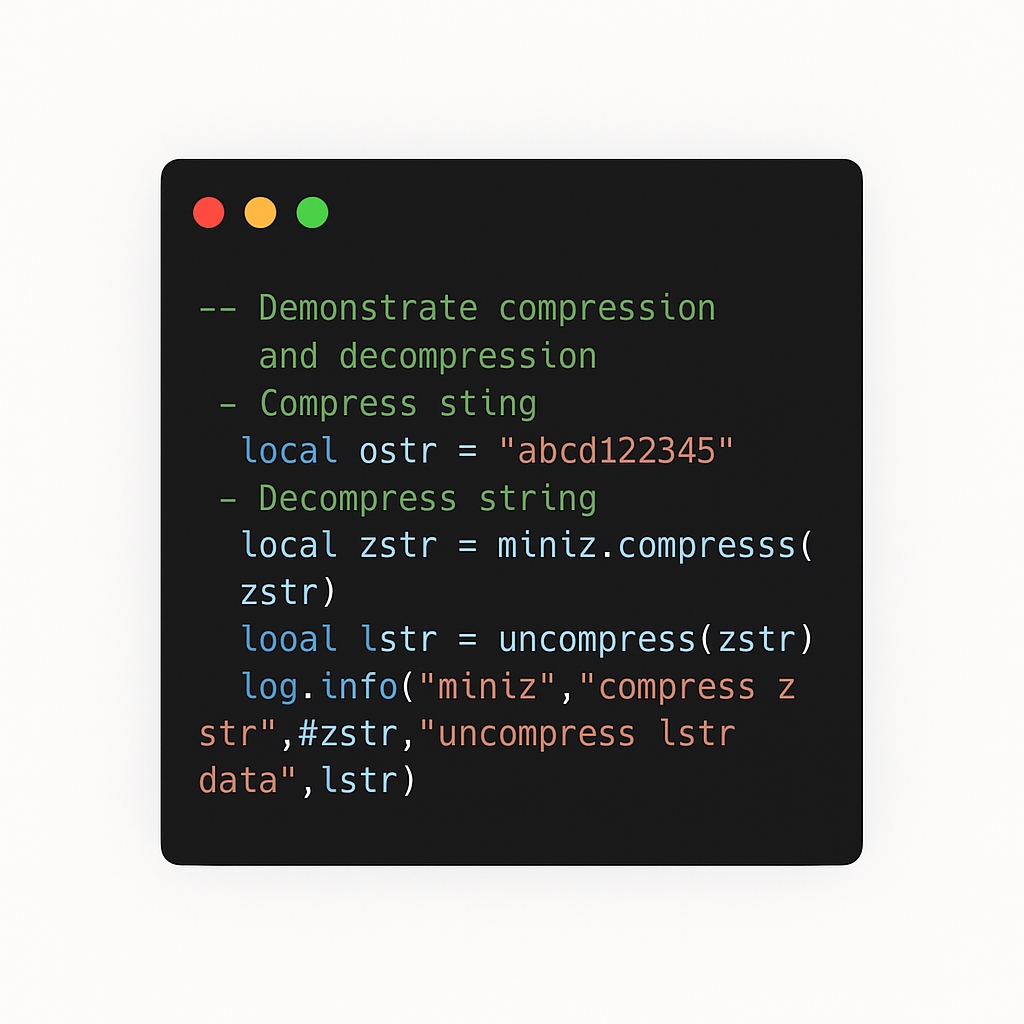

I will describe a practical example of improving the architecture of an embedded device application.

I once inherited a project implemented as a single-process, multithreaded model. The project had several modules, which I will label A, B, C, D, and E. The business logic established many interdependencies among these modules.

In the initial design, module A monitored state and directly called interfaces in modules B and C to implement functionality. The convenience of direct calls in a multithreaded process encouraged this simple approach. Later a new module F needed to handle states monitored by A. Following the same pattern, the implementation steps were:

- Provide an interface in module F;

- Make module A call that interface.

This solved the new requirement quickly.

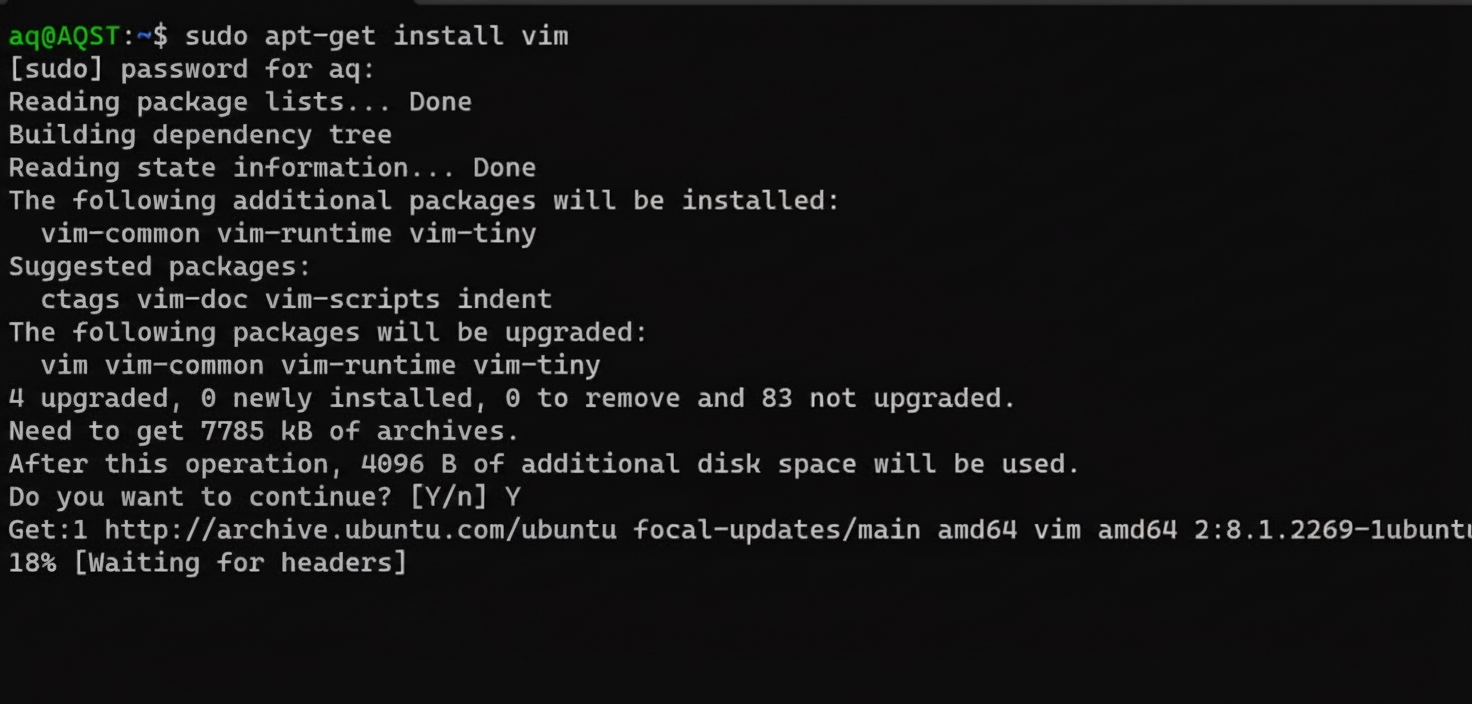

When another custom requirement arrived that introduced module G, which also needed to react to A's state but was not required by the custom scenario that used F, the simplest workaround was to introduce a compile-time macro and build two program versions. That is manageable initially, but as custom variants increase, maintaining many builds becomes a nightmare. Code becomes cluttered with macro-conditional differences such as:

#ifdef xxxdo_something;#endif

A better approach is to detect device model or version at runtime and have a single binary support all variants dynamically. This reduces build maintenance, but it does not by itself remove scattered conditional logic across the codebase. If those conditionals spread, maintenance will still be painful.

Most developers will think to extract the variant behavior into a single, centralized place. A common practice is to use callbacks and hooks, configuring which callbacks handle variant behavior. In the example, add a hook in module A; at system initialization, register different callback implementations depending on the device version. Keep those callback implementations localized in a single area so that variant handling is centralized.

This separation means changes to functional requirements typically do not require modifying module A. Adding features no longer modifies A's internal call flow, enabling loose coupling between modules. The callback approach already improves maintainability compared with the first naive design.

Is the callback approach optimal?

Software must evolve continuously. There is still room to improve beyond callbacks. First I will discuss the trade-offs between multithreaded and multiprocess models, and then describe how switching to a multiprocess model can further benefit architecture.

Why consider a multiprocess model?

For large projects I favor a multiprocess model regardless of raw performance. The main advantages are:

Reduced coupling

Multithreaded projects often exhibit direct cross-module calls. If you remove a module and try to build, you will likely find missing function calls or global variables, indicating strong coupling. Because threads share an address space, direct calls are easy and tempting. Developers sometimes remove static qualifiers for convenience and directly reuse functions. Over time, cross-module dependencies increase and coupling rises.

In contrast, a multiprocess model physically enforces separation. Inter-process communication (IPC) is harder than direct calls, so developers must think carefully about whether an interaction is necessary and how to define clear interfaces and protocols. This constraint encourages better interface design and reduces coupling by design.

Extracting common components

When converting a multithreaded design to multiprocess, you will often find duplicated interface code across processes. The remedy is simple: extract shared interfaces into a library. This extraction produces reusable common components and clarifies the separation between common infrastructure and independent business modules.

Fault isolation and accountability

In a multithreaded process, if one thread crashes the whole process can exit. Tracing responsibility across teams becomes difficult and can lead to blame. With multiple processes, if a service process crashes, it is clear which process failed and who should investigate. Fault isolation improves ownership and reduces inter-team disputes.

Performance and debugging granularity

When overall process resource usage is high, identifying which thread is responsible can be hard, especially on embedded platforms with limited tooling. With multiple processes, resource usage maps to processes, making it easier to identify and diagnose the offending component. Breaking a system into processes reduces per-process complexity and simplifies troubleshooting.

Distributed deployment

Although embedded systems often run on a single chip, there are cases where functions are distributed across multiple chips. A multiprocess architecture extends more naturally to distributed deployment. Conceptually, embedded systems are already distributed: various components interact across interfaces rather than a single monolithic app.

Code access control

Multiprocess separation can support code permission isolation within a company. While ideally companies trust their engineers, practical considerations may require some isolation of implementation details. Packaging common functionality as libraries is reasonable, but exposing business-specific modules as libraries may not be desirable.

These advantages are not absolute; multiprocess models are not always superior for every metric. However, the multiprocess model forces engineers to think more about design by making inter-module communications explicit and more costly.

How to migrate the example to multiprocess

The first question is how to choose an IPC mechanism. Linux provides many IPC options. For control messages and low-volume communications, sockets are a good choice. On the same machine, Unix domain sockets are convenient, and they also make future distribution across machines easier.

However, naively replacing direct calls with sockets between every pair of modules leads to a complex web of connections. Each module would need to connect to every other module it communicates with, creating a maintenance nightmare similar to the multithreaded case but more cumbersome.

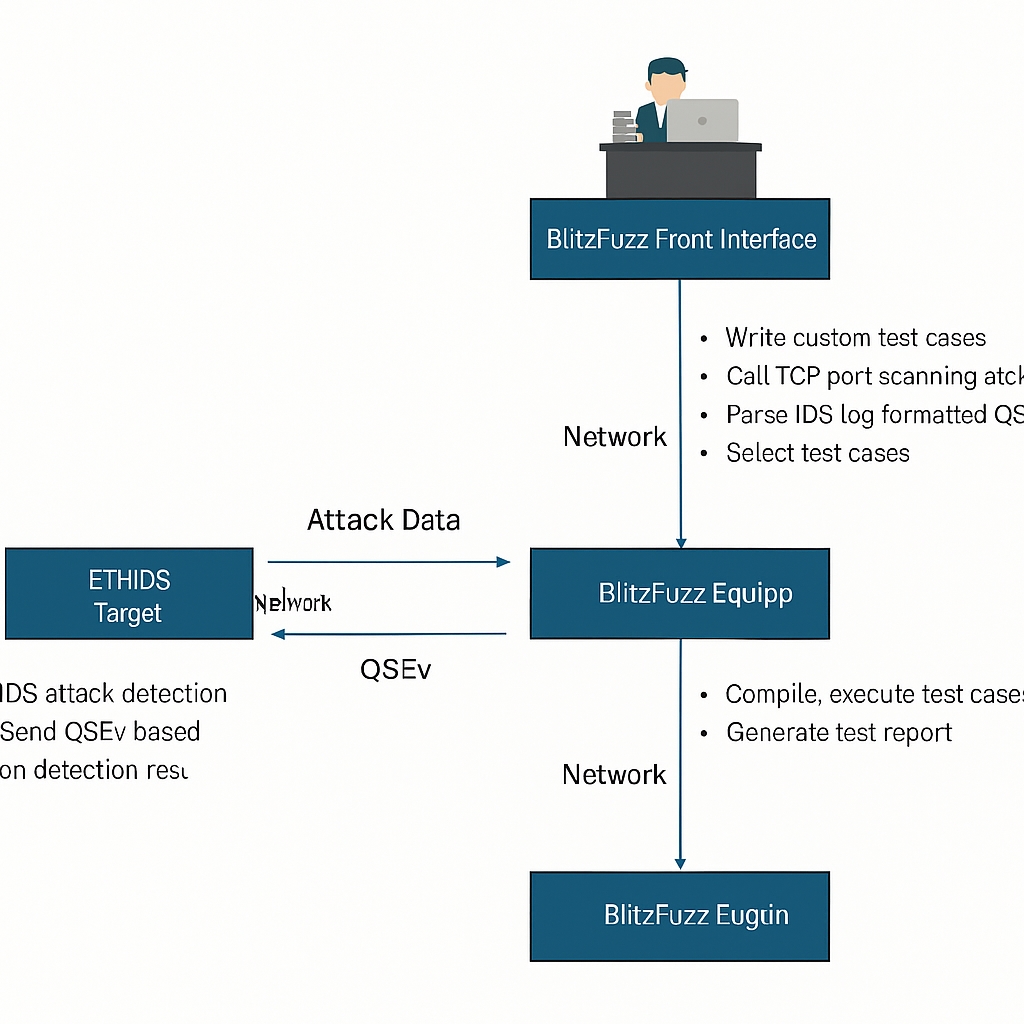

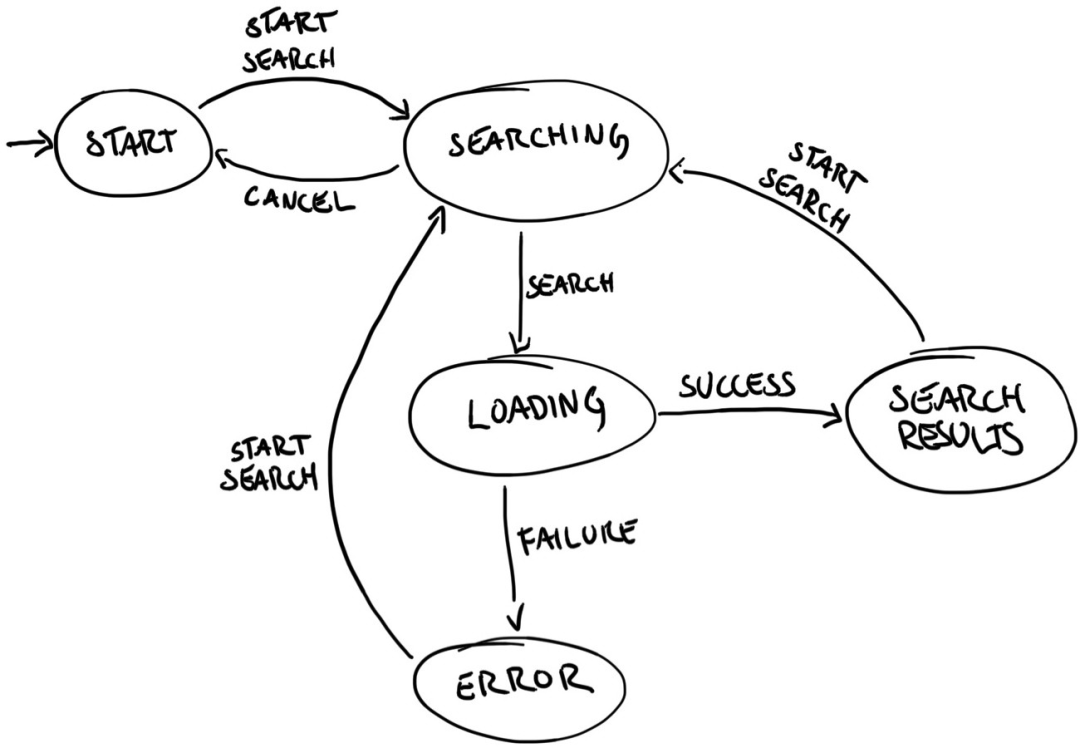

A better solution is to introduce a message bus or message center. Examples at different levels include Android Binder, OpenWrt ubus, desktop D-Bus, and the pub/sub mechanism in Redis. The idea is to establish a central message router. Modules do not communicate directly; they connect to the message center and use a publish/subscribe observer pattern to define routing rules.

Some embedded and C developers mistakenly think design patterns only apply to object-oriented languages. Design patterns such as publish/subscribe and observer are language-agnostic and apply equally to C-based embedded systems.

With a message center, modules B and C subscribe to events published by A. When A detects an event, it publishes it to the message center, which forwards it to B and C. Adding module F or G only requires starting that process and subscribing to the relevant events; A does not need modification. Customization is then a matter of starting or not starting processes, making feature addition as simple as plugging in or removing modules. This modularity localizes changes and prevents widespread code modification.

Lessons from the internet industry

In large web systems, architects often split a monolithic application into finer-grained services based on business domains, then deploy those services on multiple servers for concurrency and scaling. That is analogous to converting a multithreaded app into separate processes or services.

After splitting, communication between services becomes a major concern. Many middleware solutions implement pub/sub, RPC, and similar patterns. The core challenges are designing protocols and optimizing performance. Load balancers in web architectures can also be seen as a form of message routing and distribution.

The key point is that software design principles are consistent across domains. Although embedded business logic is often simpler, careful thought can still yield significant architectural improvements. Some embedded developers accept suboptimal practices because they work in the short term. That mindset can be limiting. Even when a simplistic approach suffices initially, better architectural practices make systems more maintainable as requirements evolve.

Conclusion

There should not be an unbreachable wall between embedded and internet industry practices. The focus should be on common software engineering principles such as decoupling, modularization, clear interfaces, and suitable IPC models. Embedded systems do need architecture, and adopting architectural thinking can significantly improve maintainability and extensibility.

ALLPCB

ALLPCB