Overview

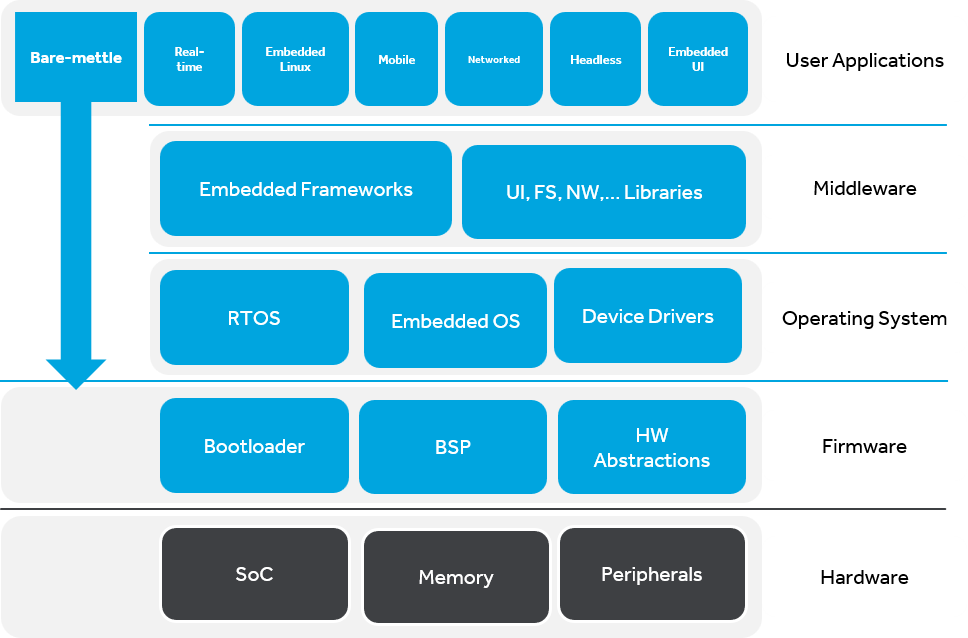

From 3D rendering to image warping, the capabilities of modern graphics display controllers (GDCs) are essential for a wide range of innovative applications. High-end GDCs help define product style and perceived value through complex dynamic graphics, while more modest GDCs present clear, simple information efficiently and cost-effectively.

Graphics requirements range from basic QVGA display ICs with pre-rendered graphics and optional video input, through midrange GDCs paired with WVGA displays (primarily 2D dynamic graphics with possible 3D features and video input), up to controllers supporting SXGA or higher resolutions with dynamic 3D graphics and multiple inputs.

Cost-Sensitive and High-Performance Architectures

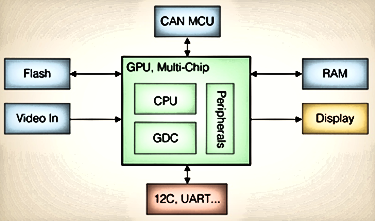

Some applications are highly cost-sensitive, such as automotive systems where minimizing the bill of materials is a priority. For entry to midlevel applications, designers can meet this requirement by using single-chip SoCs with on-chip graphics controllers. These GDCs can communicate with other vehicle systems over the CAN bus and may support low-power sleep modes to preserve battery life.

Bottlenecks such as internal VRAM capacity and bus speed limit supported graphics feature levels, flexibility, pixel fill rates, and display size. When performance outweighs cost, high-end SoCs with multi-chip architectures are preferable. These GDCs rely on an external vehicle MCU for tasks such as CAN handling, power management, and stepper motor control. They typically lack on-chip VRAM and program flash, instead using high-speed VRAM interfaces to support high performance.

Choosing a basic GDC option can balance cost and performance for many applications.

Performance Considerations and Color Depth

Certain application domains, notably automotive, must match the high-end graphics experience users see in smartphones. Designers must ensure the GDC can produce smooth, crisp graphics and that the system can respond quickly to user inputs. The GDC must not become a system bottleneck that introduces latency in the user experience.

For entry- to midlevel applications, a single-chip SoC may be appropriate. High-end applications typically require a multi-chip architecture with external VRAM and flash to meet performance demands.

When a display supports 24-bit RGB input, a GDC with 24-bit RGB output helps avoid banding (sudden shifts between tones of the same color). Using 24-bit color ensures smooth-looking graphics. Otherwise, the application may need a dithering function in the GDC to counter banding. Dithering applies randomized noise to the framebuffer to prevent banding caused by limited color depth.

Although elaborate, smooth graphics are attractive, applications that prioritize robustness and usability—such as many industrial electronics—can be well served by more basic graphics functionality. Low-end GDCs can provide surprisingly strong performance for many uses without increasing bill of materials cost.

Static or Dynamic Graphics Content?

GDC selection also depends on the nature of the graphics content. If content is static and known in advance, low-cost GDCs (for example, sprite engines) may be sufficient. Pre-rendered graphic bitmaps can be stored in external flash for a sprite GDC. These controllers are adept at handling various color formats, including palette-based formats and framebuffers with actual pixel values, and they can handle transparency and alpha blending. Using low-overhead compression schemes, such as run-length decoding (RLD), can significantly reduce storage requirements for pre-rendered graphics and lower cost.

Other applications require dynamic graphics determined at runtime, such as maps or procedural animations. These applications need GDCs with full-featured pipelines capable of rendering 2D or 3D models using texture mapping. Hardware features like lighting and fog can be beneficial. For complex tasks, graphics engines with shaders offer greater flexibility.

Flexible display controllers simplify graphics implementation and enable better visuals. In particular, flexible layering schemes and support for multiple layers, alpha planes, and various color depths make graphics development easier.

2D vs 3D

Choosing between 2D and 3D graphics affects the performance and feature requirements of the GDC. 3D applications require higher vertex processing rates and features such as perspective-correct texture mapping and mipmapping. Mipmaps are sized, optimized versions of a primary texture stored alongside it; they help avoid costly runtime texture resizing and improve performance.

Adding a z coordinate for 3D significantly increases processing demands. 2D rendering is much simpler and—if content is static—can often be pre-rendered as described above. For dynamic 2D or 3D content, a graphics engine with a complete pipeline is required.

Legacy Support and Discrete GDCs

Some projects must reuse CPUs from prior designs to meet legacy requirements rather than redesigning the system from scratch. These projects can often make effective use of standalone GDCs without an integrated CPU, communicating with a host CPU over memory, PCI, or PCI Express buses. This approach enables scalable designs with a range of performance levels and feature sets.

Some applications require the display to be physically remote from the GDC. In such cases, high-speed serial links like APIX can transmit video to the display. This configuration supports a client/server architecture where the GDC acts as the server and the display as the client. Developing client and server systems separately can reduce software and cost on the server side, since a single PCB can be extended across a product family. Integrating a high-speed serial output in the GDC makes this implementation efficient.

Conclusion

The current range of GDC capabilities makes device selection a key part of application development. A variety of GDC options exist to meet different application domains, enabling designers to balance feature sets, performance, and cost.

ALLPCB

ALLPCB