Overview

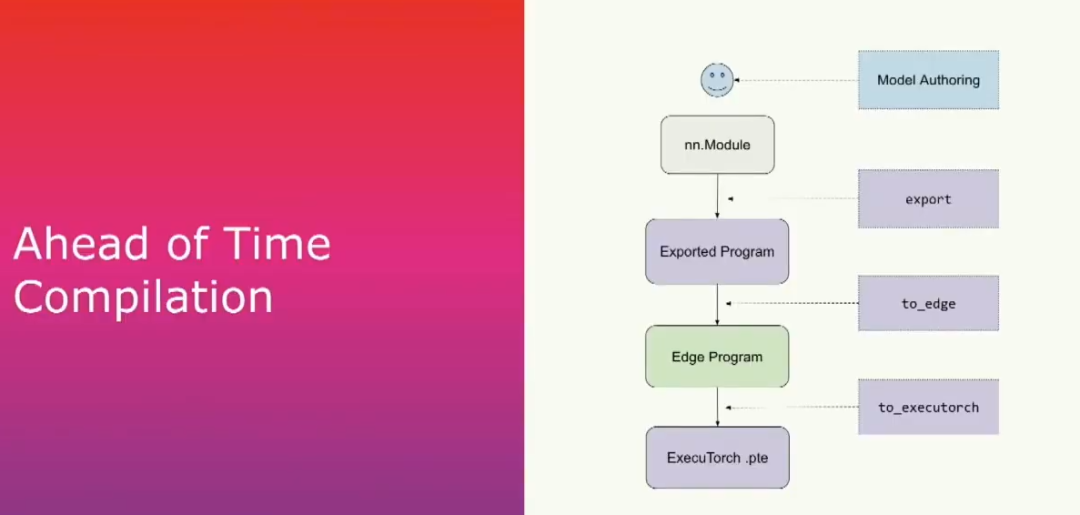

For developers, the ExecuTorch technology stack is divided into two phases. First, a PyTorch model is prepared, typically as a torch.nn.Module. From that model we capture the computation graph and lower and serialize it into an additional torch binary. This completes the ahead-of-time compilation phase. The binary is then placed on the device and executed with the ExecuTorch runtime.

Ahead-of-time compilation stages

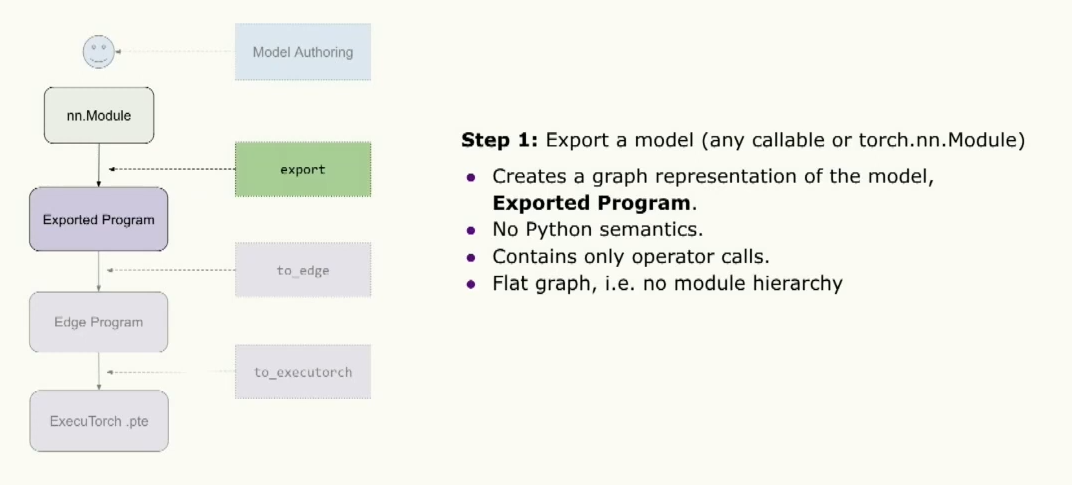

The ahead-of-time compilation has three main steps. First is export, which captures the computation graph for a given model (such as an nn.Module or other callable) using the PyTorch2 export mechanism. Internally this stage enumerates all active operations and produces an exported program, which will be discussed in more detail below.

The second step is a call to to_edge, which produces an edge program that serves as the entry point for most ExecuTorch users to run optimizations and transformations. The final step is to_executorch, which converts the program into a binary file with a .pt extension. That file is then passed to the runtime.

Exported graph representation

The export step creates a graph representation of the model. This representation is an fx-style graph that contains no Python semantics, allowing it to run without a Python runtime. The graph contains only operator calls, so constructs like module calls or method calls are eliminated. The product of export is an exported program that resembles a torch.nn.Module.

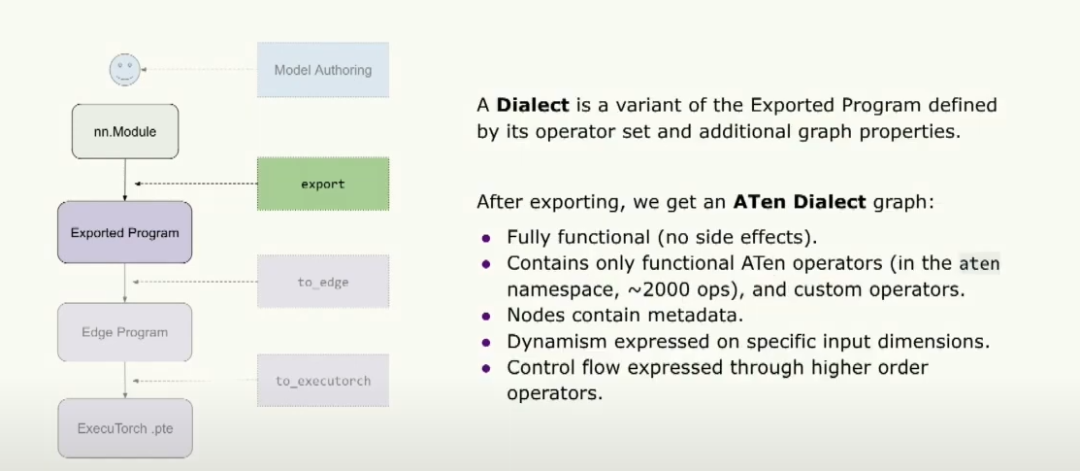

The generated graph variant is referred to as the Aten Dialect graph. By dialect we mean a variant of the exported program defined by its operator set and additional graph attributes. By Aten we mean the graph contains only torch.ops.aten operators, and those operators are purely functional, i.e., without side effects or mutation. This set includes on the order of 2,000 operators. Graph attributes include metadata such as a pointer to the original model stack trace and output data types and shapes for each node. Dynamic behavior and control flow on specific inputs can also be expressed using higher-order operators. For more details, see the Torch Expert presentation.

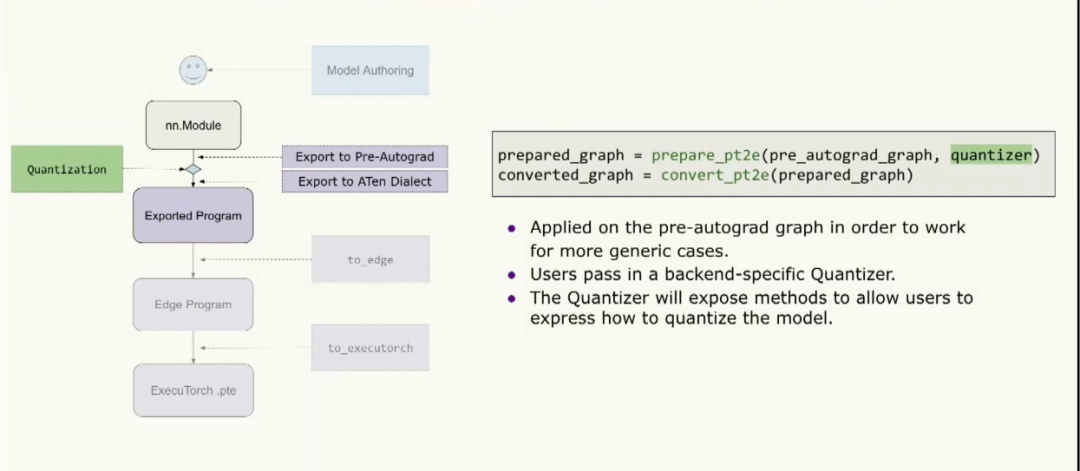

Quantization and lowering

Quantization runs at an intermediate exported stage because it needs to work on a higher-level opset, which is also safer for cases such as training. The workflow exports to a pre-autograd representation that is safe for training, then runs quantization, then lowers to the Aten Dialect and passes the result to the rest of the ExecuTorch pipeline. The API resembles PT2E: the user supplies a quantizer, PT2E transforms it, and the transformed graph proceeds through the stack. The quantizer is backend-specific and indicates what can be quantized on a given backend and how. It also exposes methods that allow the user to express how they want the backend to perform quantization.

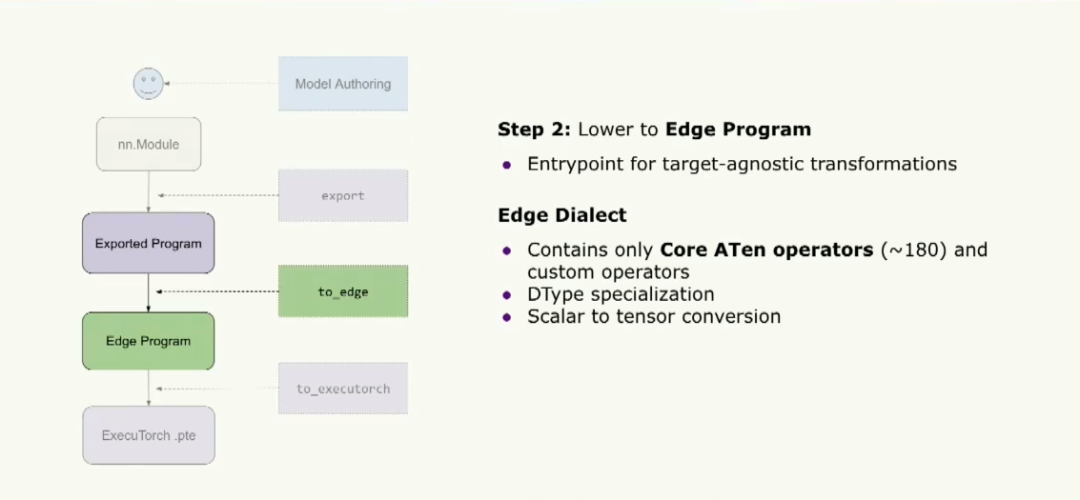

Lowering to Edge Dialect

The next step is lowering to the Edge program, which is the entry point for ExecuTorch users to run target-agnostic transformations. At this stage we work with the Edge Dialect, which contains a core set of Aten operators—about 180 operators. If you are implementing a new backend for ExecuTorch, implementing these roughly 180 operators is sufficient to run most models, instead of implementing the full Aten set.

The dialect also supports data type specialization, which allows ExecuTorch to generate optimized kernels for specific dtypes. Inputs are normalized by converting all scalars into tensors, so kernel implementations do not need to handle implicit scalar normalization.

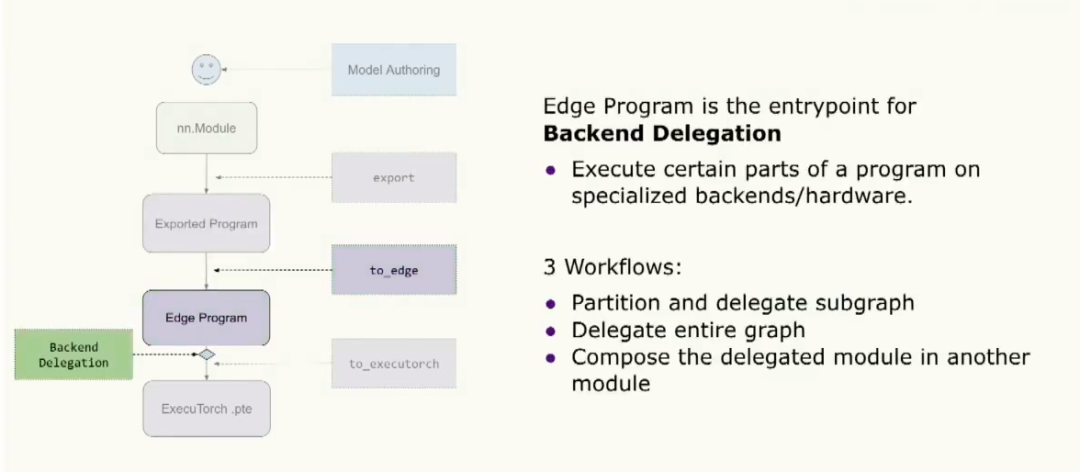

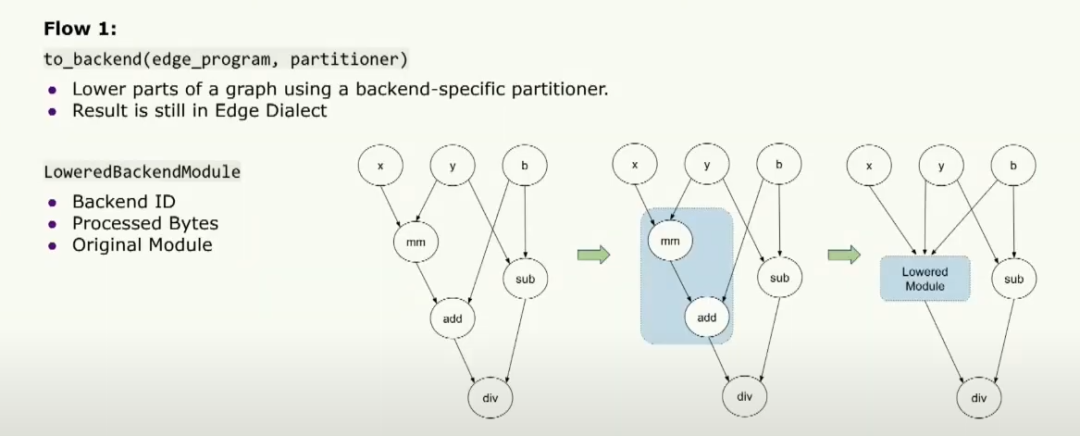

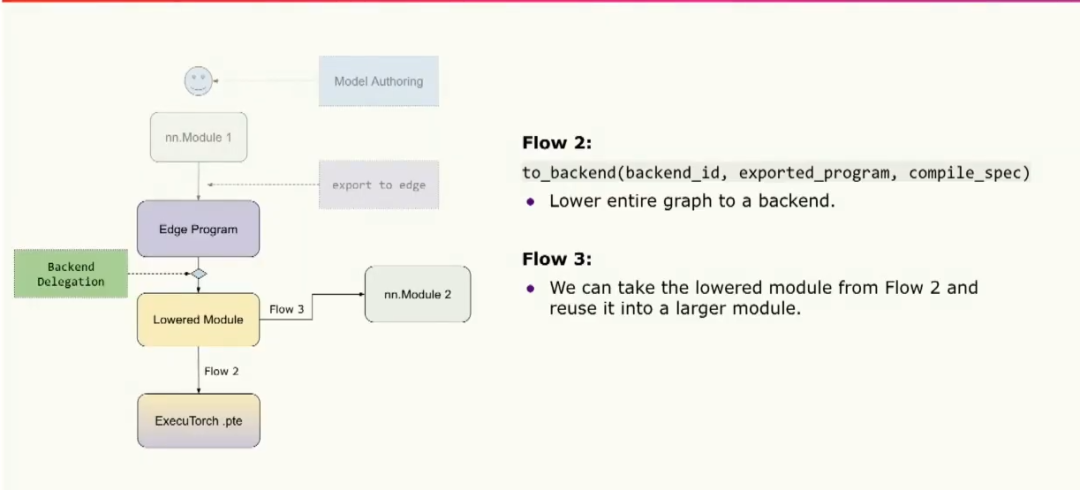

Backend delegation

Another entry point for the edge program is backend delegation, where users can choose to optimize and offload part or all of the program to specialized hardware or a backend. There are three common workflows: partitioning the graph and delegating parts, delegating the entire graph, or a hybrid approach where delegated modules are composed into a larger module for reuse.

In the partitioning workflow, the user can provide a backend-specific partitioner that indicates which operators can run on the backend. The to_backend API partitions the graph according to that partitioner, lowers those partitions into a lower-level backend module, and passes that module to the runtime. The module includes a backend ID, identifying the backend to run on, and a set of processed fragments that describe exactly what must run on the specialized hardware. The module also contains the original module for debugging.

The second workflow lowers the entire graph to your backend and directly converts it to a binary that is passed to the runtime for execution on specialized hardware. The third workflow composes fully delegated modules into other modules for reuse.

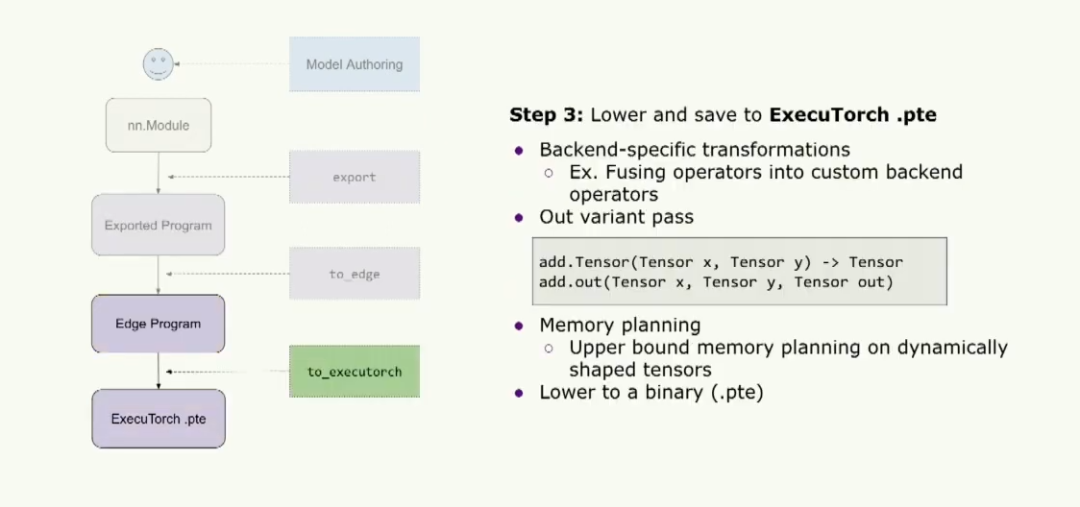

Executable format and memory planning

Finally, the graph is converted and saved as an ExecuTorch binary. Users can perform backend-specific transformations ahead of time, such as fusing operators into a custom backend op. A custom memory planning pass is then run to determine how much memory the program requires. To prepare the graph for memory planning, an out-variant pass converts all operators to out variants. This simplifies memory planning because many typical operators, such as add.tensor, allocate the output tensor inside the kernel. Using an out variant expects a preallocated output tensor to be passed in, allowing the kernel to assign results into that tensor. With this approach, tensor lifetimes can be computed and the program's required memory can be determined ahead of time, avoiding dynamic allocations at runtime. The final binary can be stored with a .pte extension and passed to the runtime.

At this point we expect to have a .pte file. The runtime is the next stage to examine.

Runtime goals

Assuming developers can produce the ExecuTorch binary, the next question is how to run it on target devices. Target devices may expose different capabilities: some may have only a CPU, others a microcontroller, and some specialized hardware. The ExecuTorch runtime must compile and run on all of these platforms.

After ensuring the runtime builds on a target device, developers may ask about special hardware topologies, for example two memory regions where one is very fast but small and the other is large but slow. The runtime should support such hardware configurations and provide customization options developers need.

Devices are often resource-constrained, so efficiency and performance are critical. The runtime is therefore designed with performance, portability, and customizability in mind.

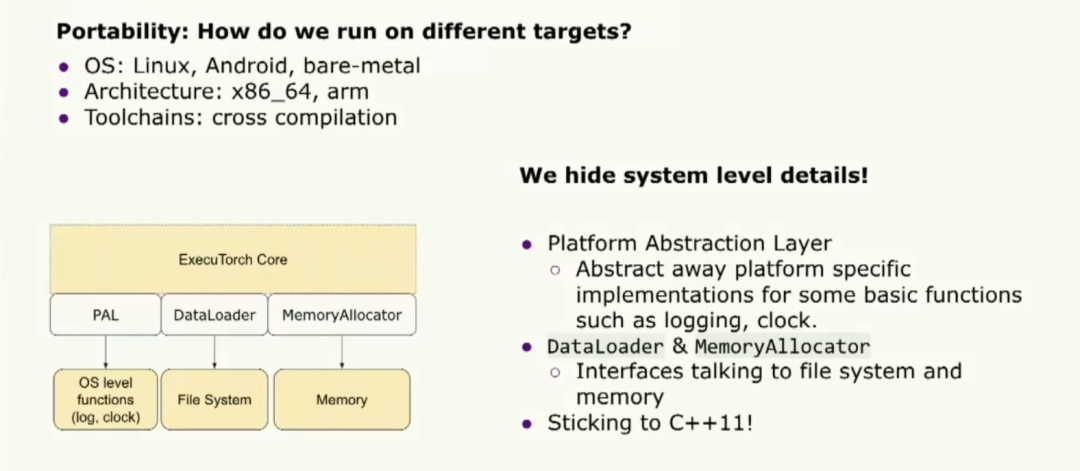

Portability

Target devices include different operating systems, architectures, and toolchains. To satisfy portability requirements we hide system-level details behind a platform abstraction layer. This layer exposes a unified API for basic functions such as logging and clock access, and it abstracts many platform-specific implementations. The runtime also provides data loader and memory allocator interfaces for communication with the host OS. ExecuTorch runtime follows the C++11 standard to remain compatible with most toolchains.

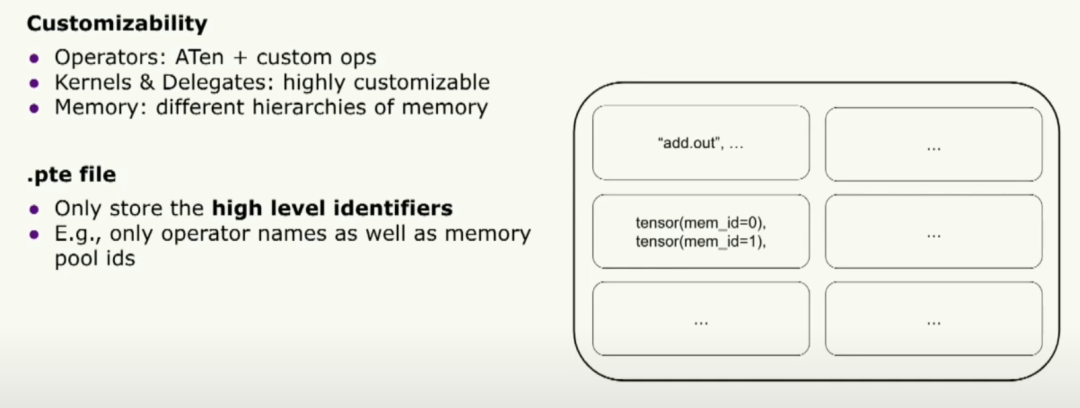

Customization

The ExecuTorch binary is the single bridge between compile-time and runtime. To support customization we designed the binary to contain only high-level identifiers: operator names and memory pool IDs, leaving runtime implementations pluggable. This enables extensive customization at runtime.

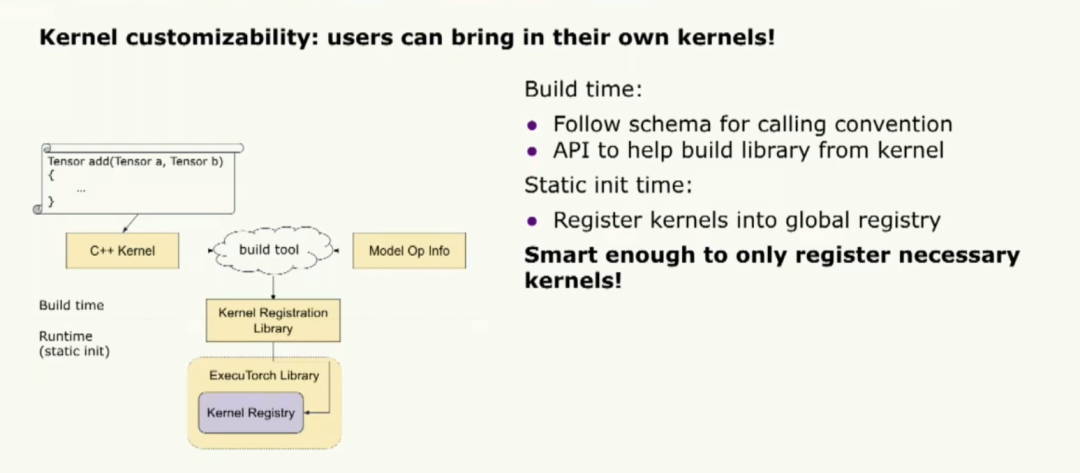

Kernel customization is a key feature. Users can bring their own kernels. ExecuTorch supplies an internal portable kernel library that is not optimized for peak performance; users can register their own optimized kernels instead. Registering custom kernels follows the core Aten operator naming convention and a build tool can register the library with the ExecuTorch runtime.

If model-level operator usage information is provided, the build tool can register only the necessary kernels to reduce the binary size.

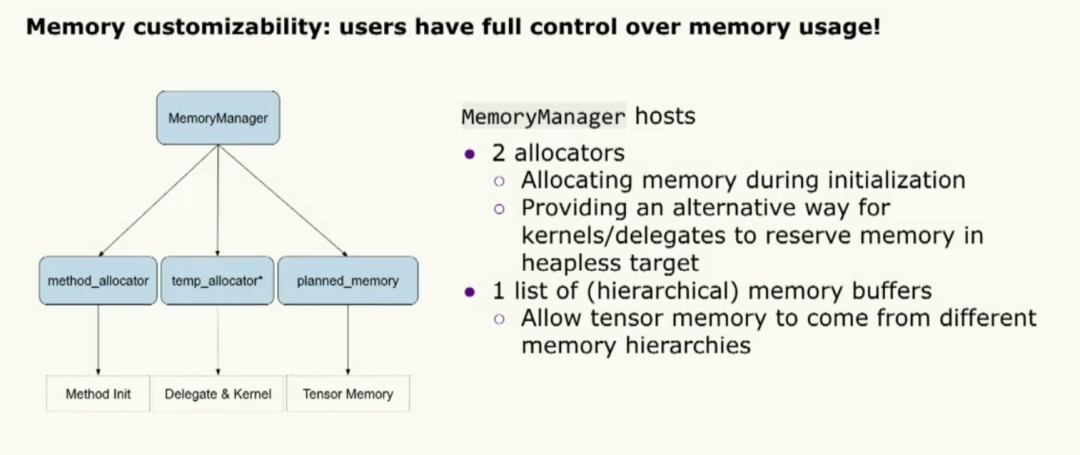

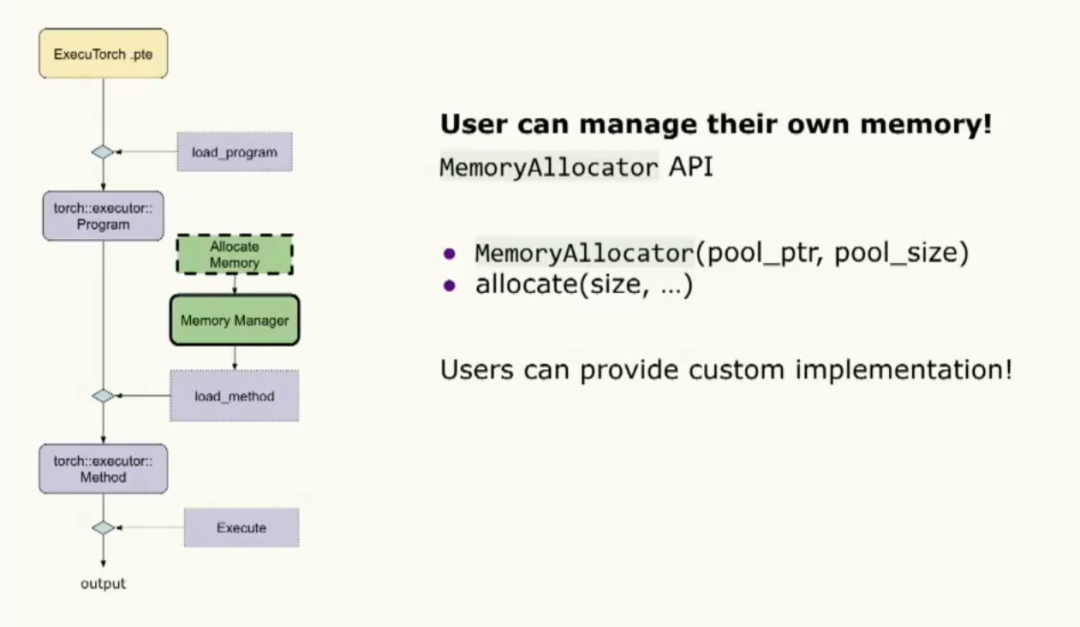

Memory customization is supported via a MemoryManager object that enables extensive configuration. The MemoryManager comprises two allocators: one for initialization and one for kernel and delegate execution. A set of memory buffers is available for tensor allocations, completing the customization surface.

Performance and tooling

To meet performance needs, the runtime minimizes overhead between kernel and delegate calls. This is achieved by preparing input and output tensors prior to execution so the user pays the setup cost once, even for repeated runs. A second design principle is to keep a small runtime binary and low memory footprint by shifting complex logic and dynamic behavior into the ahead-of-time compiler.

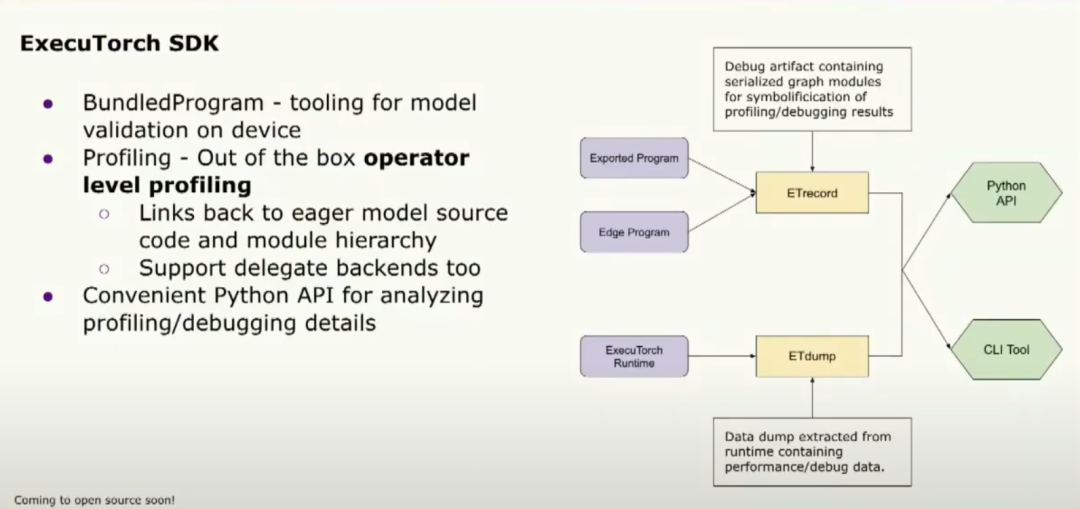

The SDK includes performance debugging tools. Useful APIs include a binder that can bind sample inputs to the model for fast execution, as well as debugging and analysis tools. The profiler attaches statistics to operators, helping to identify bottlenecks. These tools are exposed via a Python API to facilitate developer workflows.

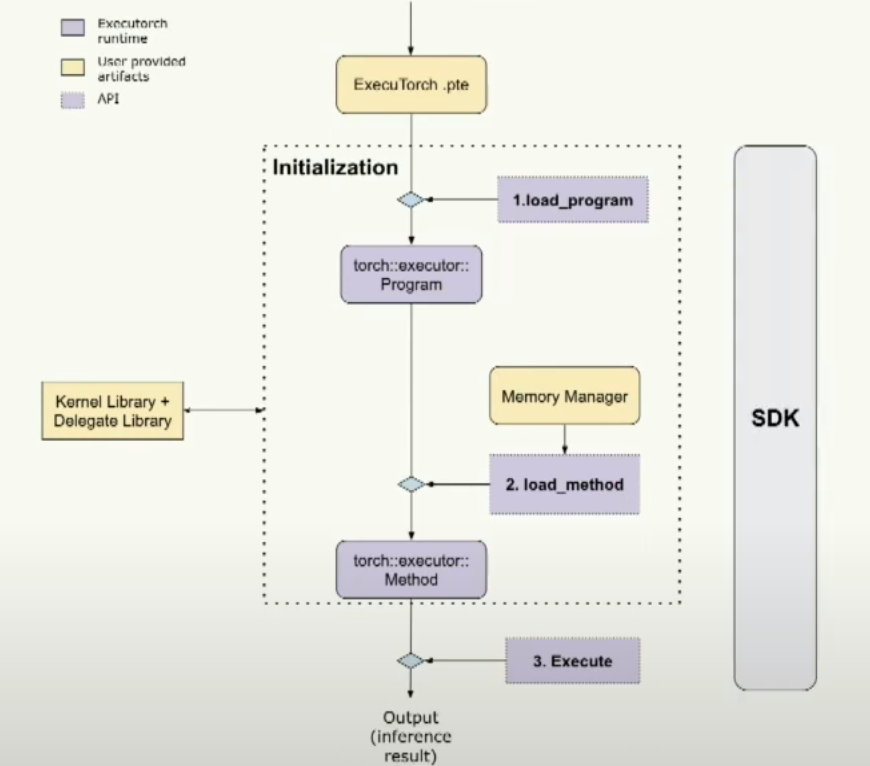

Loading, initialization, and execution

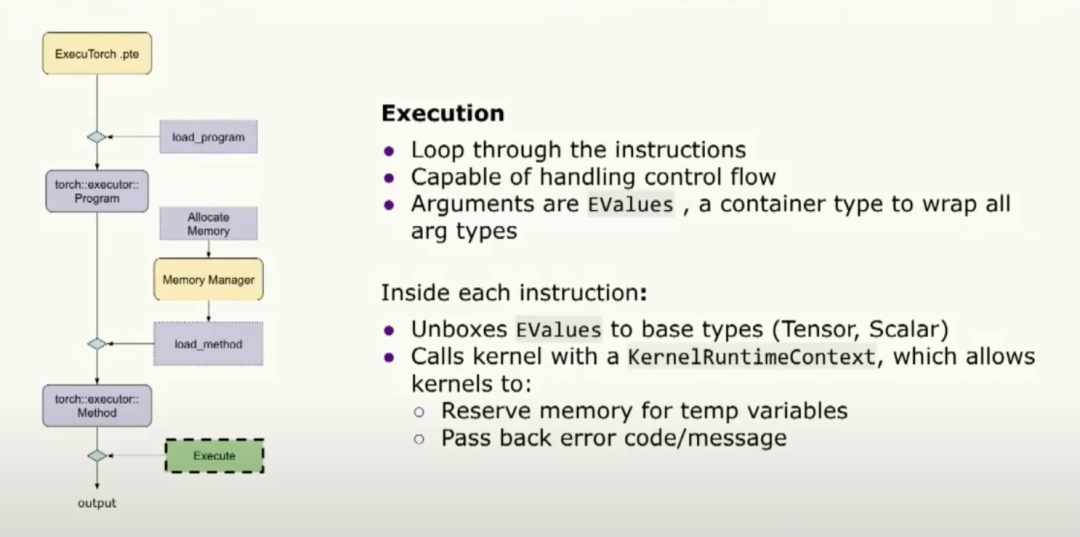

The runtime loads an ExecuTorch .pte file, performs initialization such as loading programs and methods, and then executes them. SDK tools can validate the end-to-end flow to ensure each step is correct.

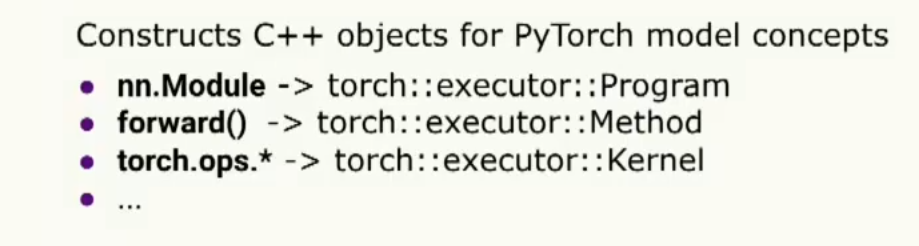

During initialization the runtime creates C++ objects that represent PyTorch concepts. The root abstraction is program, analogous to nn.Module. A program can have multiple methods; a method contains multiple operators, represented as kernel objects.

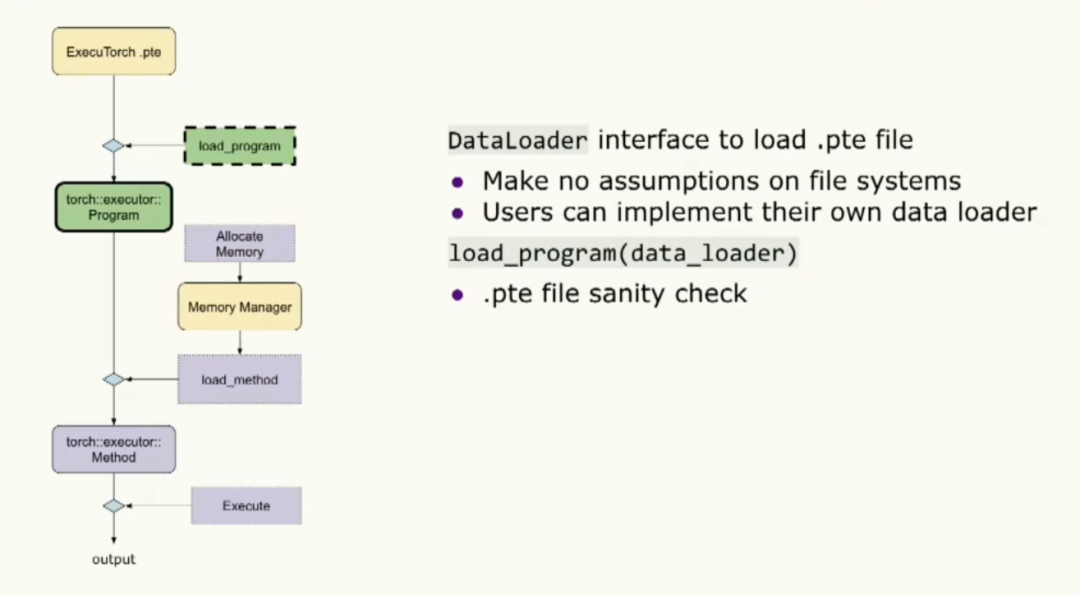

When loading a program, the runtime expects a data loader interface to obtain the binary. The runtime makes no assumptions about a file system, so users can implement the loader to suit the target device. The loader performs binary validation. Users can also supply a memory manager at initialization to manage their own memory.

The last initialization step is calling load method, where the developer specifies the method name to execute along with the memory manager.

Execution is a simple loop over instructions. Control flow is handled by jumping to specific instructions, and each instruction parameter is an EValue that can be unboxed into base types such as tensor or scalar. The kernel runtime context handles execution details.

Demos for Android and iOS, as well as GitHub tutorials, are available.

End.

ALLPCB

ALLPCB