Overview

Watches no longer only tell time. Smartwatches enable messaging, calls, and health monitoring, turning the wrist into a smartphone companion. Wearable devices are wireless devices that users wear almost continuously. For example, fitness trackers monitor health by measuring parameters such as heart rate, motion, sleep, body temperature, and sweat. These devices include multiple sensors and typically communicate with internet-connected devices such as smartphones or PCs. Wearables serve three primary functions:

- Always on: Fitness trackers run continuously, so battery life is a major constraint. A key challenge in wearable design is balancing power consumption with limited battery size.

- Activity monitoring: Trackers sense, process, log, and report user activity. This requires multiple sensors and sensor fusion, where data from several sensors is correlated by a DSP-like engine to analyze complex behaviors and present them in usable ways.

- Data exchange: Conveying collected and analyzed information to other devices, for example sending notifications to and from a smartphone.

Example system architecture

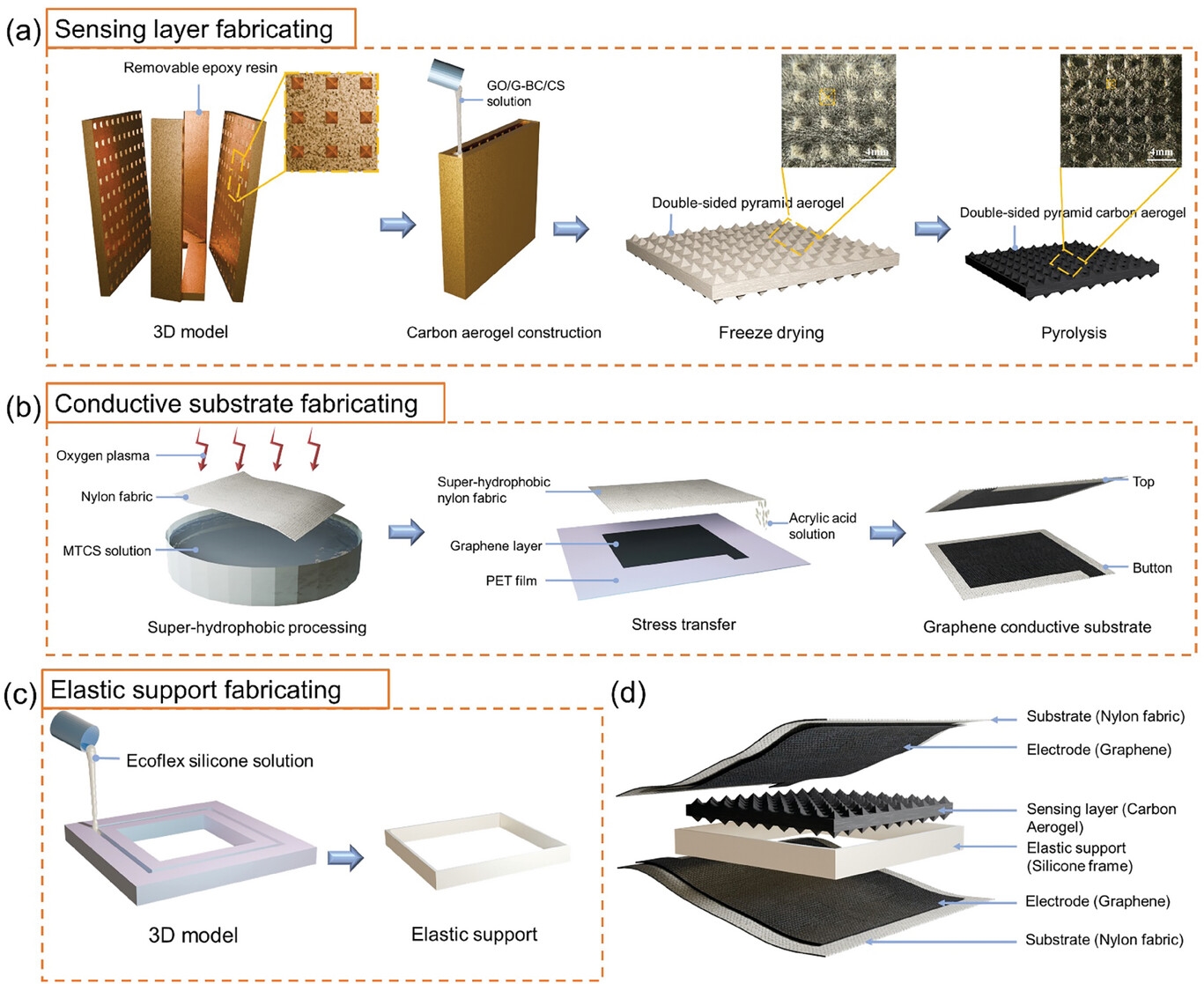

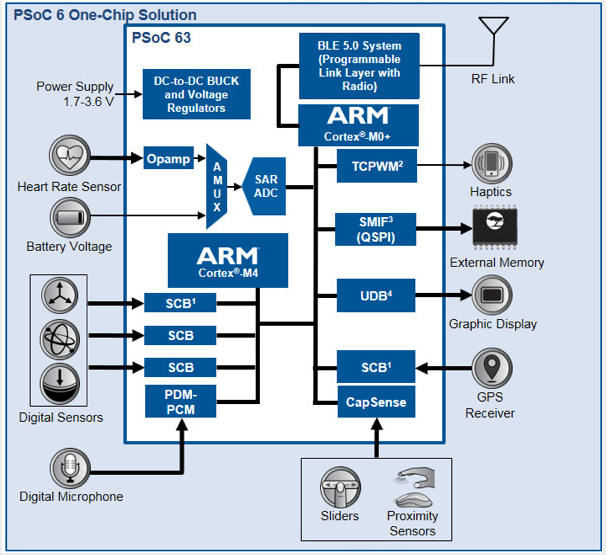

Figure shows a wearable fitness monitor implementation based on an embedded MCU such as a PSoC 6 BLE.

Sensors and interfaces

Activity monitoring: Pedometers and calorie counters compute steps and estimated calories burned. Step detection requires an accelerometer. Pressure sensors are used to measure elevation changes during walking or running. Most sensors provide a digital interface, commonly I2C, SPI, or UART. Collected data requires additional filtering and processing to compute steps, altitude, and calories. Sensors also support low-power system behavior, for example waking the system on detected motion. To support multiple sensors, the embedded MCU needs several configurable digital interfaces and ideally the ability to map pins between I2C, SPI, and UART for maximum sensor selection and implementation flexibility.

Dual-core support is desirable so that one core performs sensor fusion and complex analysis while a low-power core handles system tasks such as motion wake-up.

Environmental monitoring: The monitor may collect ambient data such as UV exposure, ambient temperature, barometric pressure, and compass heading.

GPS: GPS modules usually provide a UART interface and supply position (latitude and longitude), speed, and altitude.

Audio: Audio signal processing in the digital domain is essential for any audio subsystem before wireless transmission. Data is often captured with PDM microphones and then measured, filtered, or compressed. An embedded MCU with integrated DSP and audio features simplifies design of a continuous high-quality acoustic subsystem.

Security: Wearables must support evolving security protocols. An embedded MCU with secure boot can ensure only authenticated code runs on the device. The device can also support over-the-air updates.

User interface: Modern users expect buttons, sliders, and touch-sensitive displays. Embedded MCUs can support various display technologies such as e-ink and OLED.

Wireless connectivity: Devices need low-energy Bluetooth (BLE) connectivity and the necessary services for wearable operation.

Firmware flow

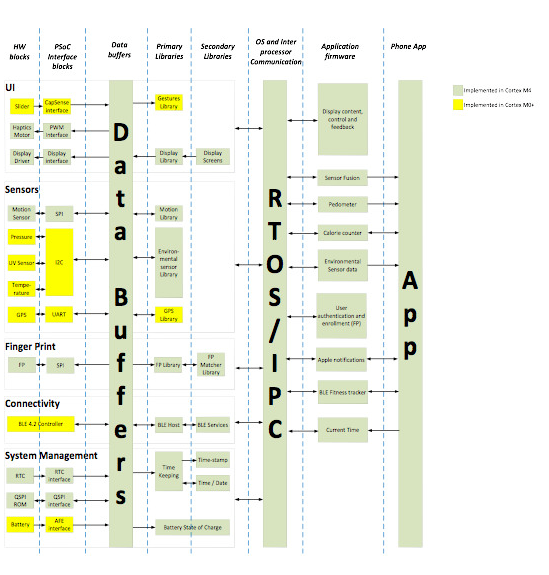

Supporting these functions requires a comprehensive firmware flow, shown in the diagram below.

Task architecture

Any wearable design centers on three key tasks:

- Acquire data

- Process data

- Communicate with the user — input and output (display)

Sensor acquisition often requires higher processor operation rates than other tasks because processing includes running filters on large sample bases. A low-power core such as an Arm Cortex-M0+ is more energy efficient for sensor data acquisition. Processing complexity dictates tradeoffs between power efficiency and performance. For realtime operations, a higher-performance core such as an Arm Cortex-M3 or M4 may be needed. User interface tasks are typically lightweight and can run on either core but are preferably on the low-power core. For optimal performance in low-power wearables, a dual-core architecture is recommended. A dual-core setup also allows pipelining of firmware tasks to improve responsiveness and reduce resource usage and power consumption by sharing resources such as clocks, RAM, and flash between cores.

Low-power core tasks

The low-power core runs a simple task scheduler for frequent, low-bandwidth tasks such as:

- Sensor data acquisition

- Capacitance sensing scan and processing

- BLE link-layer controller maintenance for connections and advertising

- System management including security tasks and sensor control

When data acquisition completes or an event requires communication with tasks on the high-performance core (for example gesture detection), the low-power core forms a message packet and sends it to the high-performance core via IPC. The high-performance core raises an interrupt, processes the message packet, and routes data to the appropriate task running on that core.

High-performance core tasks

The high-performance core runs a real-time operating system to manage tasks such as BLE host, motion processing, display updates, GPS, barometric/temperature, UV, and fingerprint detection. Except for BLE, motion sensing, and fingerprint tasks, many high-performance tasks wait for data from the low-power core.

- BLE tasks may run periodically, once per connection interval, and then suspend until the next required wake.

- Motion tasks may be event-driven, running whenever the motion sensor generates an interrupt. Motion sensors with an on-chip digital motion processor collect data in an on-chip FIFO and interrupt the high-performance core at a preconfigured rate. The motion task reads the FIFO via SPI and processes data to compute orientation, steps, and calories.

- Fingerprint tasks run on demand when a user registers, verifies, or deletes a fingerprint. They may also run when a registered fingerprint is used to unlock the device.

- Display tasks are event-driven and run when a screen update is required or when the low-power core reports a capacitive gesture event.

- GPS, barometric/temperature, and UV tasks are quasi-periodic; they are triggered after the low-power core collects sensor data and can therefore run periodically on the high-performance core.

Inter-processor communication architecture

Two concurrently running cores require mechanisms to protect shared data and synchronize communication. A dual-core architecture should support IPC mechanisms such as locks, message passing, and interrupt/notification. Task code can use IPC locks to protect shared data and IPC message passing to exchange notifications and data between cores.

IPC locks: When a core attempts to modify shared data, it attempts to acquire the corresponding lock. If the lock is free, the core gets access to the data. After updates are complete, the task releases the lock so other pending tasks can access the data. This prevents concurrent updates from corrupting shared data.

IPC messages: Beyond protecting shared data, cores need a way to synchronize tasks. This is achieved by passing command-and-parameter message packets between cores. When one core requires action from another, it packages the operation ID and parameters into a message and sends it via IPC. Once the message is ready, the sender triggers an IPC interrupt on the receiving core, which parses the command and performs the requested action.

ALLPCB

ALLPCB