Question 1

An LED mounted in a plastic enclosure wall is connected to a circuit board by a 30 cm pair of unshielded twisted pair. The LED driver generates a single-ended 3.3 V, 50 MHz PWM signal. Radiation emissions exceed the limit by nearly 50 dB at frequencies above 250 MHz. Which of the following measures is likely to bring the product into compliance?

- a. Increase transition time

- b. Place a ferrite bead on each conductor

- c. Place a ferrite choke on the twisted pair

- d. Replace the twisted pair with coaxial cable

Answer: d.

The primary radiator in this case is an unbalanced driver on the PCB driving what is effectively a balanced cable. The twisted pair, relative to the PCB ground plane, develops a common-mode voltage. Replacing the twisted pair with coaxial cable maintains an unbalanced source-to-LED connection and prevents a common-mode voltage with respect to the PCB ground plane.

Because the radiation peak occurs at the 5th harmonic, option a (increasing transition time) has little effect on the signal amplitude at 250 MHz. Ferrite beads on the signal line may provide some loss at 250 MHz, but any loss sufficient to achieve 50 dB attenuation would also prevent the LED from lighting.

A ferrite choke around the pair near the PCB can suppress resonance and reduce common-mode current; however, achieving 50 dB attenuation at 250 MHz would require an impractically large common-mode impedance and no suitable ferrite is likely to be available.

Of the provided choices, coaxial cable is the only viable option. Another practical choice is shielded twisted pair: shielding does not stop the common-mode voltage from appearing across the conductors, but it provides a return for the common-mode current inside the cable shield back to the PCB, preventing radiation. In many cases, the best approach is to drive the LED at a much lower frequency; if the drive frequency is a few hundred hertz, any common-mode voltage on the drive cable is irrelevant.

Note: The LED mounted in the plastic wall is small and can act as a balanced element that develops some common-mode voltage, but its contribution is negligible compared with the common-mode voltage driven by the cable.

Question 2

At high frequency, which field component above a metal surface has a magnitude approximately equal to the surface current density?

- a. Magnetic field

- b. Tangential electric field

- c. Normal electric field

- d. Total electric field

Answer: a.

At the boundary of a good conductor, the tangential magnetic field is perpendicular to the surface current and has the same magnitude. The normal component of magnetic field is zero, and the tangential electric field is also zero.

The normal component of the electric field relates to surface charge. |εE| equals the surface charge density, and current is the product of charge density and frequency, but field strength (V/m) is not the same as surface current density (A/m). One practical consequence is that discontinuities on a metal surface change the local surface current direction and create high current density at those locations. A magnetic-field probe can be used to detect peaks in current density and locate gaps that compromise enclosure shielding.

Question 3

A 100 MHz electromagnetic wave is incident on 5 mm thick transparent glass with relative permittivity εr = 8. What is the shielding effectiveness of the glass?

- a. 0 dB

- b. -3 dB

- c. 3 dB

- d. 6 dB

Answer: a.

A thin glass plate is negligible compared with a quarter wavelength at 100 MHz, so it produces almost no attenuation. There is no significant absorption loss because glass is a very poor conductor. The front-surface reflection coefficient is about 0.5 and the back-surface reflection coefficient is about -0.5; for a thin plate these contributions cancel.

Note that at roughly 5.3 GHz a 5 mm glass plate corresponds to a quarter wavelength. At that frequency the path-length effects change the reflection contributions and the shielding peak is on the order of 4 dB.

Question 4

If the rise time Tr of a 10 MHz trapezoidal waveform is increased from 1 ns to 5 ns, by how much can the maximum amplitude of harmonics above 320 MHz be reduced?

- a. 0 dB

- b. 5 dB

- c. 7 dB

- d. 14 dB

Answer: d.

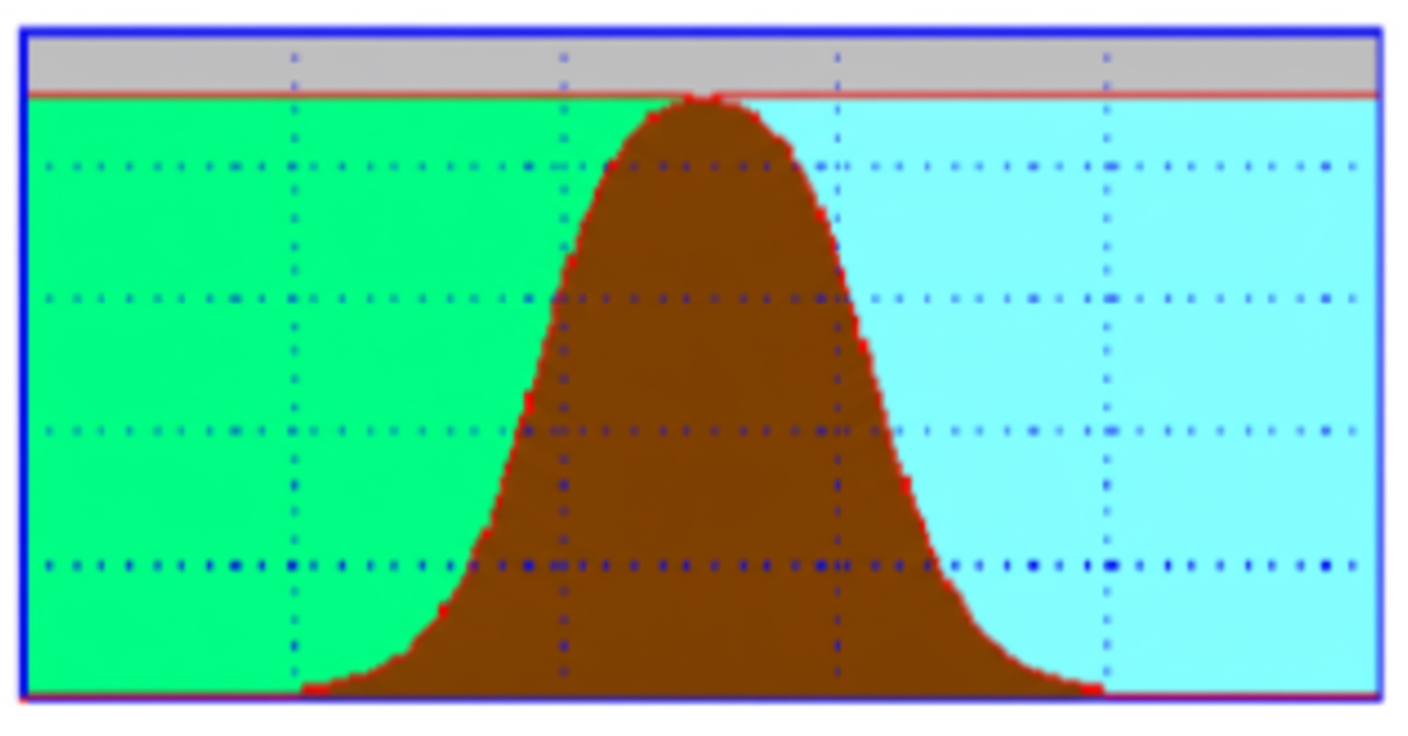

Harmonics of a trapezoidal wave roll off at 20 dB per decade above roughly 1/(pi·tau) until the transition-time cutoff frequency f_c = 1/(pi·tr). For tr = 1 ns, f_c ≈ 318 MHz. For tr = 5 ns, f_c ≈ 64 MHz. For frequencies above both cutoffs (here, above 318 MHz), the maximum harmonic amplitude ratio equals the ratio of transition times, which is 5. Converted to decibels: 20·log10(5) ≈ 14 dB.

Default behavior for most digital sources is transitions faster than 1 ns. Controlling transition times to reduce high-order harmonic amplitude is often important to minimize crosstalk and radiated emission problems caused by very fast edges.

Note: The 14 dB reduction is for the envelope (the maximum amplitude). Individual harmonics may move relative to the envelope because changing the transition time shifts the locations of zeros in the harmonic spectrum; some harmonics can increase while others decrease, but all lie at or below the envelope.

ALLPCB

ALLPCB