Overview

This article describes unique challenges in designing wearable devices and how to optimize power efficiency to reduce device size. It covers the importance of operating voltage and how to choose an appropriate regulator. It also explains the importance of battery state-of-charge metering and concludes with examples of highly integrated devices optimized for ultra-portable and wearable applications.

Introduction

As people turn to electronics for entertainment, physical activity can decline and lead to health problems. While technology can contribute to sedentary behavior, it can also help address it. Electronic pedometers and fitness trackers encourage more activity by reporting activity levels, and there is evidence supporting the effectiveness of this approach.

The number of wearable fitness tracker options continues to grow, and many devices add simple step counting and other features to encourage activity. For any of these devices to be effective, they must be used. To achieve user adoption, they need to be unobtrusive and low-maintenance: small and light enough to be forgotten, and able to provide long runtime between charges to minimize charging hassle. Battery energy available is proportional to battery size, so extending time between charges without increasing size or weight is challenging. Since the battery is often one of the largest components in a wearable, designers must carefully balance the power budget and size.

This article discusses how to reduce the size and weight of wearable devices without degrading performance. Achieving those goals can improve device usage and produce a positive impact on public health.

Design Challenges

To reduce size and weight, wearable designs must minimize battery energy consumption so a smaller battery can be used. In many respects wearables are like any other battery-powered application, but their scale is much smaller and requires different optimization levels.

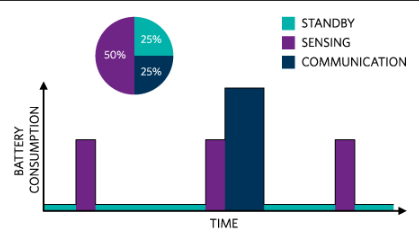

Wearables must quickly serve higher-power tasks and spend as much time as possible in idle or sleep modes. The available current in such devices is typically much lower than in typical mobile applications. To get a week of runtime from a 50 mAh battery, the average current needs to be below 300 μA. Allocating 25% of the power budget to standby yields less than 75 μA for idle. A regulator with a static quiescent current (IQ) of 30 μA would consume nearly half of that budget, favoring low-IQ linear regulators. Although standby consumption is tens of microamps, the system usually has peripherals that require tens of milliamps for short peaks, such as displays or radios. Without the efficiency of a buck regulator during active periods, meeting the communication power budget is difficult. Therefore, optimizing power across a wide dynamic load range requires tradeoffs and careful attention to detailed power specifications.

Figure 1. Illustration of expected time spent in three different operating modes for a wearable monitor device.

Lowering Voltage

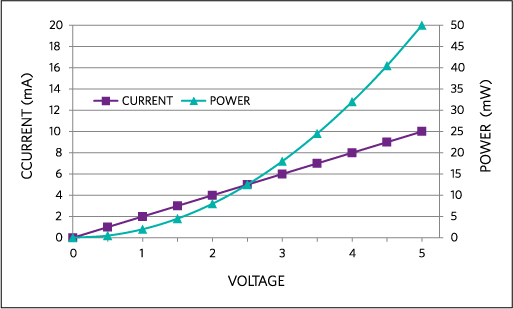

Components in a wearable require power whether active or idle. To reduce battery load we must minimize power. Power equals voltage times current, and current often scales with voltage. Thus power often varies approximately with the square of voltage. Plotting the current and power of a resistor versus applied voltage makes the dramatic difference between current and power easy to see.

Figure 2. Current and power versus voltage for a 500-ohm resistor.

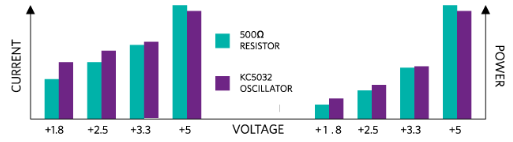

Although active devices are not purely resistive, the current needed to charge and discharge capacitors also depends on applied voltage. Many active devices have power that varies with the square of the applied voltage. Comparing the current and power of simple active devices such as a KC5032 oscillator with those of a resistor shows an example of this behavior. This voltage-squared relationship partly explains why computation per watt improves when voltage is moderately reduced. It also explains why using a linear regulator to lower voltage can reduce power even though conversion efficiency is poor, since input current is essentially equal to output current for a linear regulator.

Many devices regulate voltage internally for power savings and other reasons. Internal regulation is often linear, minimizing current changes. Even so, total power still scales with input voltage. Generally, selecting components that support the lowest practical operating voltage and running them near the low end of their input range helps minimize system power.

Figure 3. Comparison of current and power between an oscillator and a resistor.

Choosing the Right Regulator

Choosing the right operating voltage is important, and so is choosing the regulator that generates that voltage. As noted, internal linear regulation can lower consumption by allowing internal circuits to draw less current. However, linear regulation cannot fully exploit the benefits of reduced voltage. Because current through a linear regulator is the same on input and output, input power equals input voltage times current. The useful output power is output voltage times current; the remainder, current times the input-output voltage difference, is dissipated by the linear regulator.

A switching regulator is needed to fully benefit from reduced voltage. Historically, universal switching regulators could easily consume the entire standby power budget, and because wearables spend such a high percentage of time in standby, designers often sacrificed active efficiency and used low-IQ linear regulators. Fortunately, buck regulators with quiescent currents below 1 μA are now available, eliminating the tradeoff between active and standby efficiency.

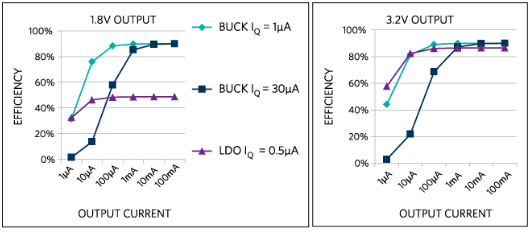

Moving to a low-IQ switching regulator can dramatically reduce battery current. If components can operate at 1.8 V and the power source is a rechargeable LiPo with an average voltage near 3.7 V, battery current can be nearly halved. But buck regulators are not always the best solution, particularly when the output voltage is greater than 80% of the input voltage. Buck regulator efficiency is often around 90%. When regulating from 3.7 V down to 3.2 V, even a linear regulator can reach about 85% efficiency and does not require an inductor. The efficiency versus output current plot shows that for loads below 1 mA, a 1 μA buck regulator has a clear advantage when regulating to 1.8 V, while there is little difference at 3.2 V. Because these devices spend long periods in standby, a 1 μA buck regulator is a good choice for a 1.8 V output, while the reduced PCB area of a linear regulator may make it the better option for a 3.2 V output. Note that not all switching converters are equal; inspect converter behavior under specific operating conditions.

Many microcontrollers include integrated regulators, but internal regulators are not always the lowest-power option. Reviewing the details of an internal regulator is as important as reviewing external options. When core voltage drops below 1.8 V, switching from a linear regulator to a switching regulator can reduce core power by more than half. That is why many microcontrollers allow disabling the internal regulator. Assuming the included regulator is optimal is unsafe; succumbing to the temptation to just use the microcontroller's internal core regulator can result in significant power loss.

Figure 4. Efficiency comparison of regulators at different output voltages.

Know Your Battery

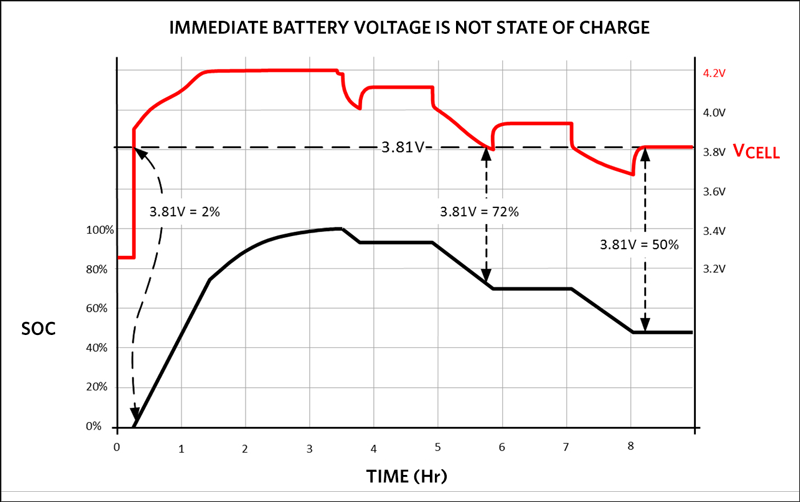

One of the worst user experiences is when a device unexpectedly stops. A runner holding a pedometer might say, "But the battery bar still looked fine." When an indicator shows remaining charge, no one wants a device to shut off. Therefore, indicator accuracy is critical. Any uncertainty in battery state-of-charge (SOC) must be subtracted from the reported available energy. To guarantee short times between charges, designers often oversize the battery to allow for measurement inaccuracy.

Because the battery is so important in system design, the chosen method for measuring battery state will directly affect size, cost, and user experience. For the tiny currents common in wearables, coulomb counting is often impractical. Voltage detection can be too small for micro-power amplifiers, and the required measurement frequency can consume too much power. Voltage monitoring techniques are often the only practical solution.

Rechargeable lithium batteries are difficult to monitor by voltage alone. Simply reading battery voltage with an ADC does not give accurate SOC, but dedicated fuel-gauge ICs are designed to meet these application requirements. Integrated proprietary algorithms such as ModelGauge provide improved accuracy for reporting battery capacity. Accurate battery SOC measurement can be invaluable when trying to keep products thin or extend time between charges.

Figure 5. Instantaneous battery voltage is not state-of-charge.

Integrating Components

Designing miniature wearables requires optimizations different from typical mobile applications. Components and specifications that were once considered minor now become key to meeting performance requirements. Not only does each function need optimization under the new power constraints, but the design must fit into the smallest possible area. There is minimal room for glue logic or even passive components, so integration becomes critical.

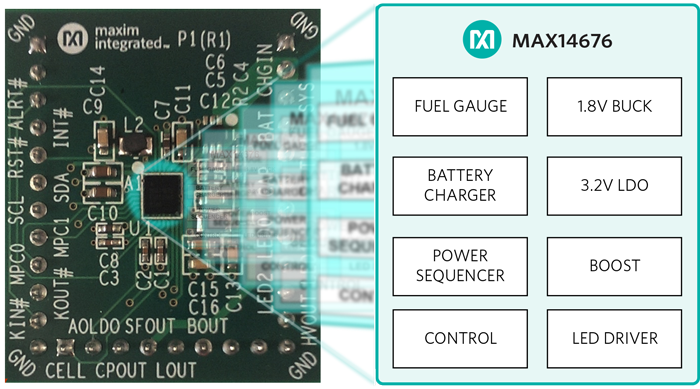

Integrated devices optimized for wearables are available. Single-chip wearable charging-management solutions combine power regulation, battery management, and monitoring in a miniature WLP package. To achieve the best regulation at lower voltages, such devices can include a buck regulator with IQ below 1 μA for 1.8 V output and a low-IQ linear regulator for 3.2 V output. For precise battery monitoring they implement ModelGauge technology. They also integrate other functions common in wearables: display/backlight power sources, power on/off monitoring, and power sequencing control. These wearable charging-management solutions help reduce battery size and weight while preserving runtime, enabling smaller, lighter, and less obtrusive fitness trackers that still meet users' needs.

Figure 6. The MAX14676 is a wearable charging-management solution integrating a buck regulator, ModelGauge technology for accurate SOC, and functions common to wearable fitness devices.

ALLPCB

ALLPCB